Christoph Huber

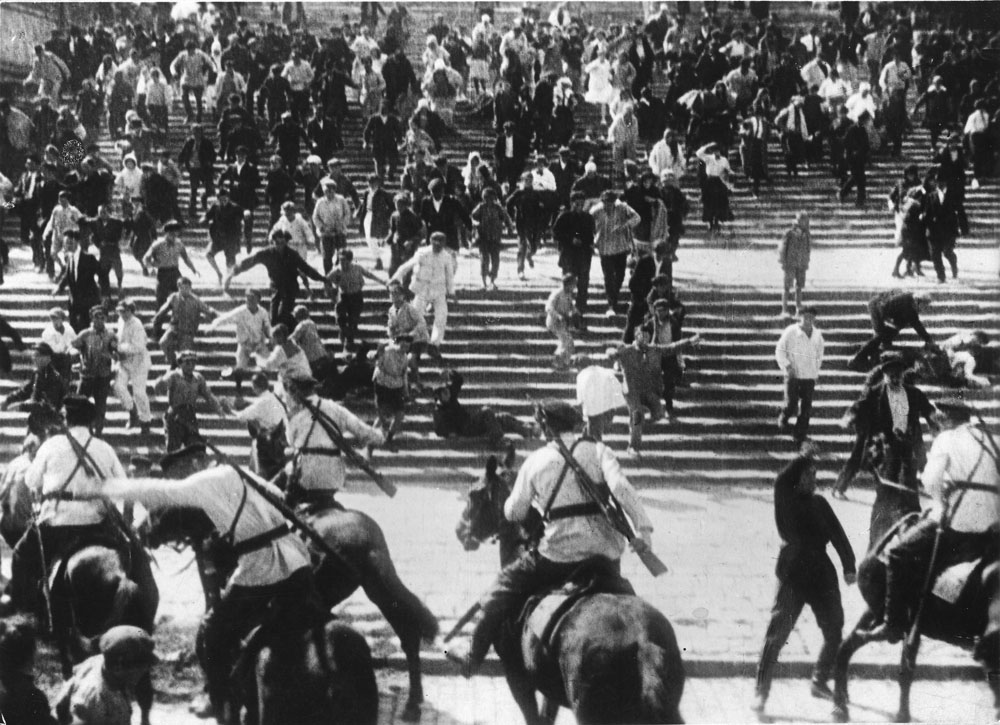

Panzerkreuzer Potemkin will never be the same: Finally having its Austrian premiere at the Film Museum, this reconstructed “Viennese Version” of Sergej Eisenstein’s classic brings together the famous images with the synchronized sound–originally coming from shellac discs–recorded for a 1930 “talkie” re-release in Germany. Most notable is the contribution of famous, and sadly short-lived composer Edmund Meisel, whose unusual combination of music with sound effects and songs leaves a literally striking impact.

For a detailed explanation of this stunning find, I refer to the real expert: Film historian Martin Reinhart, who discovered the shellacs at the Vienna Technical Museum 15 years ago, and together with his colleague Thomas Tode has since pursued this project–they will give a lecture before the screening–, was kind enough to answer three questions about the history and uniqueness of Potemkin’s “Viennese Version” (also available on subtitled DVD from Edition Filmmuseum here)–and the film project that evolved from it, Dreams Rewired, currently on the Festival circuit.

Christoph Huber: Your rediscovery of the 1930 German synchronized sound version of Battleship Potemkin in Vienna has led to a new restoration. It is quite a surprise – this version, which is also edited differently, makes quite another impression on viewers, not least thanks to the soundtrack by Viennese composer Edmund Meisel, which is quite “aggressive”. Can you elaborate a bit on the differences – and is the end result something of a “new Potemkin”?

Martin Reinhart: The 1930 sound version is based on the second German release of Potemkin, which was censored in 1928. This version for its part was a modification of the film that was shown in Berlin in 1926. Only minor re-adjustment and changes were made in order to have it re-released two years after its premiere. But the differences between these two versions are insignificant compared to the drastically new experience of the 1930 sound version. Although the only intervention on the image level was to leave away the intertitles and to increase the speed from 18 to 24 frames per second—the result of this shortening alone has an astonishing effect. The storyline becomes clearer, the film gets more dynamic and its emotional impression more powerful. Together with the sophisticated soundtrack that was recorded on Vitaphone discs (Nadelton-Platten), the film has undergone a radical metamorphosis. This is not just another variation, but an autonomous reinterpretation of Eisenstein’s masterpiece as a sound film.

The 1930 sound version is a unique example of such a transformation and it also opens a window to a vanished world: this unique mixture created from Piscator’s ephemeral Agitprop theatre, the jazz craze of the 1920’s, Brecht’s speaking choirs, recitatives, and songs, is now audible again on an authentic recording. To say it very clear: the newly restored “Viennese Version” of Potemkin is the closest approximation to Meisel’s original score in existence. Doubtlessly it will lead to a re-evaluation of all earlier attempts to reconstruct Meisel’s famous music and also have a significant impact on all future Meisel-related projects.

Christoph Huber: Meisel had composed music for the German release of the silent Potemkin version, whereas the Russian premiere had featured the usual, nearly random mix of classical music (Beethoven, Tschaikowsky, etc.). Meisel’s soundtrack seems to have made quite an impact and found the approval of Eisenstein, who even said the famous Odessa steps sequence owes “much of its power” to Meisel’s music, which was not illustrative, but created “images that are interwoven musically and optically”. Later soundtracks for Potemkin were much softer, even those based on his score transcripts. Meisel’s early death in 1930, at age 36, is a sad loss – might he have established a different approach to scoring films, possibly best described as inter-“active” instead of “passive”? And to what extent can we imagine his original composition from the rediscovered synchronized sound version?

Martin Reinhart: The Russians simply never had an interest in Meisel’s music. The communist party initiated the film for the 1925 revolutionary celebrations and later commissioned the Berlin-based left wing production company Prometheus to distribute the film outside Russia. Prometheus hired Edmund Meisel—at the time Erwin Piscator’s bandmaster—to write a score for the Berlin premiere in 1926 which instantly became a worldwide success. Eisenstein, who was in Berlin to attend the premiere worked together with Meisel on the two major scenes—the Odessa stairs and the armada sequence—but since the film was not released by the censors in time, Eisenstein’s visa expired, and he had to go back to Moscow before the film was released in Germany. The first time he actually saw his film together with Meisel’s score was at the Film Society during his visit to London in 1929.

To my knowledge, Potemkin was never screened in Russia with Meisel’s music at all—neither in the 1920’s nor after the war, but I might be wrong about that. In the 1950’s, and again in the 1970’s, the film was re-released and distributed by the Soviet State with the “true” Russian music by Nicolai Kryukov and Dmitri Shostakovich. In the West, Meisel’s score soon became a myth and a lot of effort was put in reconstructing the original composition which was considered lost. A big step forward was the finding of an authentic piano score 1983 in Dresden. This sheet music was the basis for all later interpretations. Compared to the music one can hear in the “Viennese Version” however, the earlier reconstructions sound far too symphonic and lack all of Meisel’s love for experimentation, noise music and Jazz. We know from historical sources that Meisel had rearranged his own score for the 1930 sound version, but I believe that the “hits” of his famous score remained almost unchanged and are therefore authentic.

Christoph Huber: The discovery of Meisel’s Potemkin score was the nucleus for Dreams Rewired, a film you co-directed with your collaborator on the restoration, Thomas Tode and Manu Luksch, and which just premiered at the Rotterdam Film Festival. Using archival material from over 200 films for an exploration of visionary technologies from the 1880’s to the 1930’s and their connection to the contemporary media onslaught, Dreams Rewired ended up a lot bigger in scope than expected – in what way did the final result evolve and how does the Meisel-Potemkin angle fit in?

Martin Reinhart: That really is a long story, but I try to keep it short. When I found the Potemkin soundtrack back in 2000 it was not clear what it actually was. Thomas Tode, an expert for Russian avant-garde cinema, was introduced to me by a friend, and based on my initiative the Vienna Technical Museum commissioned him to make a survey. Only after I read Thomas’ report I understood the significance of my finding and I got obsessed with the idea to bring the images and the sound back together again. This might sound simple, but it wasn’t. In my understanding the only adequate home for this version was the Austrian Film Museum, so I addressed Alexander Horwath with my idea. Alexander was very excited and in spite of all obstacles we finally were able to make the reconstruction with the help of a lot of enthusiastic friends and without any money—but it took us about 12 years to finish it! About the same time I made contact with another Meisel addict: Nina Goslar from ARTE/ZDF. Nina could not believe it when I told her that we had discovered the only existing recording of the Potemkin score and so she instantly came up with the idea of a double feature for ARTE combining the restored sound version with a 50min documentary about Meisel which Thomas and I should do. For us, it was clear from the beginning that we would not make a talking heads kind of film, and since we both are film historians we started to compile historical footage that we already knew or that we found in archives.

The idea was to tell the whole story entirely with authentic images from the past and to counterpoint them with animations made by our friends Hanna Nordholt and Fritz Steingrobe. We then contacted Marcel Beyer, the author of the wonderful novel Flughunde and asked him to write the text for our film. Piece for piece the project started to grow and the film got longer and longer. The original focus on Meisel and Potemkin became weaker and instead we dived into the whole cosmos that surrounds our main topic. We learned everything about the history of sound film—which actually starts in 1894—and discovered the incredible sound experiments that were conducted all over the world in the 1920s. So after two years spent in film archives all over Europe we had brought together a unique collection of unseen footage—about 80 hours of it! Our story became denser, wittier, and obviously too extreme. When we showed the fine cut of our movie to ARTE they were shocked how far we had gone. We have made the ultimate nerd movie for nerds. And we loved it! But since the world does not function this way, the whole project almost came to an end.

Although we fought hard, Thomas and I did not have it in us to re-arrange our movie in a way that it would please ARTE. For us, it was like tearing down our newly built house—we just couldn’t do that. So we contacted Manu Luksch and asked her for help and advice. Manu was so impressed by what we had done and understood our concept and intention. She agreed to try the impossible and, as you can see, now she did it in an incredible manner: with the utmost respect for our original work, she found a way to tell an entire new and less specialized story. She emphasized some topics that we have introduced and omitted others. Magically, she reshaped the film and turned it into an intelligent and interesting comment on the craze of today’s multi-mediality and permanent interconnectivity. By choosing Tilda Swinton as the speaker, she gave the film a unique and distinct voice that you love to listen to for hours, and Siegfried Siegfried’s score really turned the former TV-documentary in a film that you would want to see on the big screen. Thomas and I are very pleased with Manu’s work and always supported her as as much as we could. In our understanding we are completely equal creators of this one-of-a-kind film. There is still an important sequence in the film that refers to Meisel’s music, but I would not call Dreams Rewired a documentary about him.

Dreams Rewired will also have its Austrian premiere soon, playing at the Austrian Film Festival Diagonale on March 19th and March 21st.