Alejandro Bachmann

The thing that matters in both photography and history

is obviously the ‘right’ balance between the realistic and formative tendencies.

Siegfried Kracauer: History. The Last Things Before the Last,[1]

I.

In It Will Die Out in the Mind, a short work by Deborah Stratman from 2006, we mostly see a series of text fragments slowly surfacing from black in vibrating white structures (which bring to mind the grain of a videotape or a filmstrip) and then slowly dissolving again. Throughout the film it reads: „My dear, the world is unbearably boring. Don’t count on it. There’s no telepathy, no ghosts, no flying saucers. They can’t exist. The world is governed by cast-iron laws. And these laws are not to be broken. They don’t know how to be broken. And don’t count on flying saucers. Though it’d have been great. There’s no Bermuda triangle. We have triangle ABC which is equal to triangle A1 B1 C1. Do you sense the terrible boredom of this? It was interesting to live in the Middle Ages. Each house had a goblin, each church had a God. People were young. Now every 4th person’s elderly. It’s boring, my dear“. There are only two clearly visible images in that film. In the beginning, right after the title, we see a ball of fire dragging a tail behind it until it slowly dissolves back into the black that surrounds it. In the end, following the text quoted here (which was originally from Andrej Tarkovskij’s Stalker), we see a man in a desert taking off into the air with the help of a jet pack strapped to his back.

The four minutes of this film, I would argue, can be read as a highly condensed manifesto of what Deborah Stratman’s work as a whole aims for: To use the technology of film as a jet pack which allows us to call into question the cast-iron laws by which we as humans define ourselves, our history, the present world we live in and thus our potentials. While images of jet packs appeared in films long before they actually existed, their manifestation in the real world changed both the character of the fictional films (they suddenly seemed to reflect potential worlds) and our own reality (suddenly, humans could fly. Well, almost!). It was through those who looked at science-fiction films not as fictions but as possible realities and who would not accept cast-iron laws that technologies were developed which helped to reshape who we are. In the right hands, cinema can be one such technology.

II.

There is a delicacy in the way the texts appear and disappear, to the way the red fire ball fills the black screen, to the shots which Stratman chose of the flying jet-pack. They make us sensitive to the way things (objects, landscapes, people, texts) become visible (and invisible) and audible in a moving-image medium as well as to the way we deal with these phenomena as spectators. Stratman’s sense of rhythm, her feeling for durations and minor movements as well as surfaces, structures and composition inspires feelings of longing, of desire, of wonder: Do we not long for more of that image of the flying fireball once it vanishes? Do we not have to adjust to reading the words on a screen after seeing images? Do we not wonder what the industrial, drone-like sounds we hear in the background throughout the film are and are we not a little bit relieved when we can finally identify a couple of them towards the end of the work (people applauding when the man begins to fly, for example)? Cinema not only reassembles the world into possible new constellations, it seduces us into falling for them, for the aesthetic qualities of them and thus allows these constellation’s entry into our minds. Suddenly, the world does not feel quite so set into stone, suddenly it’s not quite so boring, my dear.

III.

Obviously, Deborah Stratman’s films are more than just a rejoinder to the boredom of a world governed by cast-iron laws. Her work over the last 20 years has been dedicated to using the seductive potentials of cinema to make us think about the United States of America, its history, its ideologies, its landscapes differently. She ventures out into the world, sometimes re-enacting, but more often discovering images, documents and sounds which might reveal what is hidden behind the official truth that governs things. In the editing room she assembles these disparate images into a sensual cinematographic whole so densely woven that this potential way to look at the world becomes a real possibility.

If cinema is – amongst other things – the art of light, then Stratman’s In Order Not To Be There (2002) can be seen as a cinematographic articulation of the political potential that this entails and how this aspect of cinema allows us to decode the world anew. In a 33-minute long series of mostly static shots made at nighttime Stratman decodes the landscapes of America’s white-collar universe. The darkness outside allows the film to put into focus the role light plays in the system under observation and how it makes visible that which is at its ideological centre: Lights at night emphasize the walls that mark where properties begin and end, where one should walk and thus where one is allowed to go. It highlights the effort that is put into labeling things and spaces, whether that be the entry of a gated-community or the neon-sign on the roof of a supermarket, and it makes us aware that there is no light where none of these concepts (property, commerce, etc.) apply. Stratman makes use of the light-sensitivity of the medium and creates a world that is either lit illuminated or dark, that is visible and at the same time invisible and that locates (economic and political) power where light is by default associating deviant behaviour with darkness[2].

Energy Country (2003) receives its title from yet another one of these large neon-signs that dominate dark American landscapes. But unlike In Order Not To Be There Stratman here does not carefully compose shots with a 16mm camera but rather assembles images that appear to have been made in passing with a video camera and combines them with found footage materials. The images we see – of freeways and power-lines, of neon palm tree-displays and industrial compounds, of the stock market and an oil-infested lake – melt into a stream, or rather a flow that portrays the South-Texan landscape as a system through which energy is constantly pumped. By adding conversations taken from a Christian radio-station or weaving in images from the night-time attack on Baghdad in 2003, Stratman creates a link between the currents visible on the outside to the currents that flow at the system’s core. While the aesthetic strategies applied here might seem straightforward at first, it is in their unique, careful, yet vigorous composition that Energy Country creates a feeling of restlessness, of unease, of looking at a landscape that is so charged with ideological energies that it might explode at any time. In both In Order Not To Be There and Energy Country Stratman takes the visible parts of American landscapes and composes an image of that which governs its internal structure, of the energies that circulate within it. If at the end of the video we see a man setting fire to an American flag this could be read as a blatantly direct political statement (as it is in dialogue with the two waving American flags at the beginning of the film) but is also convincingly coherent in that it finds an image in the material world that functions as a metaphor for what lurks beneath it.

IV.

Man flying resurfaces as a motif in Stratman’s films time and time again. At the centre of O’er the Land (2006) stands the story of Col. William Rankin who was forced to eject from his fighter jet in 1959, fell and then became trapped in the thermodynamic ups and downs of a thunderstorm before reaching the ground alive. O’er the Land also marks a turning point in Stratman’s work as the question regarding how far the history of the US has written itself into its present landscapes slowly comes to the foreground, reaching a peak with her most recent longer work, The Illinois Parables (2016).

O’er the Land starts with some shots of wreckage in a forest while we hear a slowly descending high pitched sinewave on the soundtrack recalling the seemingly endless but unavoidable fall from the sky to the ground. In the middle of the film a sequence of shots of clouds is combined with the description of what William Rankin has gone through on that day in 1959. In between and afterwards we see – amongst others – scenes from a reenactment of a battle involving the Régiment de Guyenne in the woods, a US-college football game, borderpatrol looking for traces of trespassers on the US-Mexican border, and an adventure park for people with a fascination for guns in action. The wreckage in the present in combination with the sound of the falling plane from the past, the re-enactment of a historic war next to a football game, the story of a soldier’s safe landing on ground followed by men with guns making their way through a staged war-scene creates a space-time continuum where the borders between what once was and what still is become blurry. The story of William Rankin, who lost control over his plane and had to hand over his life to the whims of nature brings into interplay the two forces which seem to define the American landscapes depicted – freedom and control. The idea of freedom that reigns so strongly in American history and its self-image and that articulates itself (amongst other ways) in the right to carry guns or the possibility of travelling across the country in an oversized mobile home stands in opposition to the constant control that is exerted over the body, territory and nature and which Stratman finds razor-sharp images for in America’s present and past.

The Illinois Parables picks up this interaction of past and present in an effort to re-write the history of the State of Illinois. Again, we begin with an image of flight: A mid-air pan across the vast plains of the state is followed by a couple of wide shots of mounds on ground level. A distanced, panoramic view is put into a dialogue with a closer look at that very same landscape. The seemingly endless horizon becomes blocked by an object, a mount, an overgrown pile of earth, that reminds one a bit of a molehill (which is nothing else but the visible trace of a creature that builds its world out of sight). To the viewer they feel like a marker telling him/her to stop looking at the landscape and start reading it. „They’re inscriptions, they hold a history of a place, and a really specific one that some culture has written, and they aren’t language-based“ (Stratman). Commencing from there The Illinois Parables becomes the poetic document of a research project that re-writes the history of the state by searching for (metaphorically speaking) mounts. It is the manner in which Stratman builds that history, the way she interweaves the 11 parables that are to follow, diving into the past and finding its traces in the present that seduces us to look at it differently, to feel the presence of these fragments in the here and now. From the mounts accompanied by sounds of nature she cuts to the image of a Roman number I after which we see a parking lot. The white lines demarking the single parking spaces on the asphalt take up the white abstract line on a black foreground and gently lead us into the first parable. A traditional indiginous chant slowly rises on the soundtrack until a man with a drum walks into frame introducing himself as „Ravenwolf“, a shaman, who explains that he has sung this song to be in contact with his ancestors. The film cuts into white drawings of monsters on a black background, which already hint at the second parable. The Roman number II that introduces this parable comes late (and again seems to be in dialogue with the black and white drawings described) and it is this delay and slight temporal shift that creates a feeling of a cohesive whole (the history of Illinois) despite the segmented structure. Stratman’s history of Illinois is made up of a mixture of widely known events (such as the Trail of Tears) and obscure incidents such as an unexplained series of fires (to which Stratman invents a beautiful small scene of a girl seemingly setting fire to a wall through pyrokinesis) which have left their traces in the material world of the present. The viewer thus becomes a historian and has to read images, paintings, maps and documents, has to listen to testimonies and composed sounds and connect all of them to the landscapes he/she sees. By being both accurate in her research and fluently poetic in the presentation of her findings The Illinois Parables suggest another version of a state’s history as well as another method of looking at history itself: Serious in its interest in details, protagonists and landscapes but free in its connections between those, convincing in its accuracy yet attuned to the constructedness of its form and thus history as a whole. History here is not yet another set of cast-iron laws but rather an option to be presented with alternative readings and the invitation to make connections for yourself.

V.

To call Deborah Stratman’s work “seductive“ and to see her films working towards an alternative understanding of history might raise the question of how far her artworks differ from mainstream-culture’s typical presentation of history or ideological truths. While the medium’s seductiveness has been (and still is) widely used for propagandistic means Stratman’s reworkings of history differ in that their form creates an audiovisual-experience that is both seductive (in the way she deals with surfaces, light, cadrage, sounds, music and makes use of montage to create transitions, juxtapositions, friction) and reflexive at the same time. Just look at how O’er the Land brings in the position of the spectator in the opening scenes of the battle reenactments and the football game, thus emphasizing that these spectacles of war and power are always created for someone, an audience. Or the way she uses sound and image in Chapter X of The Illinois Parables, where the killing of activist and revolutionary Fred Hampton is told through intertwining testimonies from members of the police as well as the Black Panthers on the soundtrack with a staged re-enactment which – more than anything else – becomes a reminder of how very complex it is to access the events in the past through actions in the present: Versions and perspectives from both the past and the present are put side by side, they overlap and intertwine but never fully fuse into one coherent narrative.

If one looks at some of the shorter works, such as Village, silenced (2012) or Hacked Circuit (2014) this line of reflexivity becomes even more apparent. The former takes a scene from Humphrey Jennings The Silent Village (1936) and implements a loop which lets the people on screen go through the same procedures, gestures, actions time and time again, while the soundtrack changes and thus creates different frames of references to their actions. HACKED CIRCUIT then takes up the seminal sequence of Gene Hackman’s deconstruction of his own apartment in The Conversation (1974) and turns it into a moebius-strip-like reflexion on the relationship between film, reality and surveillance as an act of control. Once again the way the 15 minute single-shot elegantly travels through the world (from a street on a city’s fringes to the studio of a sound-engineer at work with a foley artist on the scene mentioned above) is seductive in its smooth and yet controlled movement, draws us into the setting Stratman has created. Yet the whole setup calls into question the reliability of the filmic medium itself, the relationship between the world we see and the sounds we hear. We are both drawn into the film and distanced from it, we fall for the medium and its appearances while reflecting on how its technical and ideological structures work on us. We are drawn into a state of undecidability, a constant fluctuation between seemingly contradictory perspectives that seems to pay tribute to the complex paradoxical nature of cinema itself.

[1] Siegfried Kracauer: History. The Last Things Before the Last. Oxford University Press 1969, p. 56

[2] For the larger implications of Stratman’s investigation into how light is distributed and a society’s use of illumination see: Jonathan Crary: 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep, Markus Wiener Publishers, 2013, p. 4/5: “In the late 1990s a Russian/European space consortium announced plans to build and launch into orbit satellites that would reflect sunlight back to earth.(…) In any case, this ultimately unworkable enterprise is one particular instance of a contemporary imaginary in which a state of permanent illumination is inseparable from the non-stop operation of global exchange and circulation“.

Originally published in Swedish for Magasinet Walden

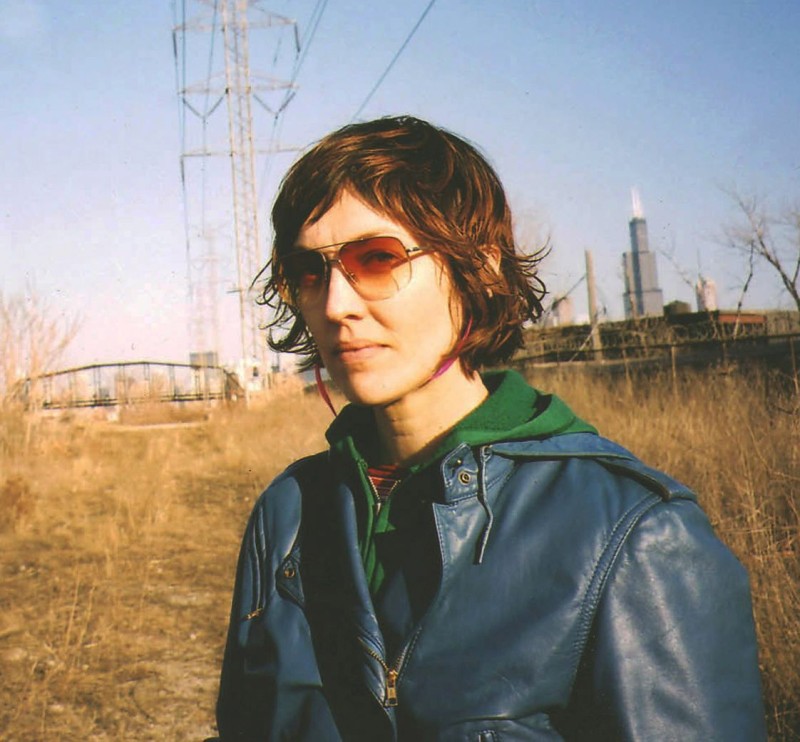

In Person: Deborah Stratman @ Austrian Film Museum