Tom Waibel

When Animal Farm was completed in 1954 at John Halas and Joy Batchelor’s animation studio, it was the first full-length animated feature in England. Let’s keep in mind that up until then, fewer than 30 full-length animated feature films had been made throughout the history of cinema, and about two-thirds of them were produced in the United States. So how did it happen that the commission for a feature-length political satire in animation format was given to a rather small (British) studio that had previously produced mainly World War II propaganda cartoons?

Let’s take a look at the process of making the film, starting with the remarkable story of its literary basis, the world-famous success story of the same name by George Orwell, according to whose own account “this book was first thought of, so far as the central idea goes, in 1937.”

That year, George Orwell, whose civil name was Eric Arthur Blair, had gone to Spain to fight the fascists who had risen up against the country’s elected democratic government. Orwell fought on the side of the Trotskyist-Communist POUM, and when the Stalinist-Communist Soviets took control of the Republican government, the leftist forces that Orwell had joined were violently suppressed. He himself eventually had to flee Spain to save his life. These experiences turned Orwell, a democratic socialist, into a convinced anti-Stalinist, shaped his view of the Soviet Union as a totalitarian state, and matured in him the desire “upon my return from Spain to expose the Soviet myth in a story that could be easily understood by anyone.”

Orwell completed this story in the early summer of 1944, at a time when the Soviet Union had crushed the fascist German armies at Stalingrad, thus changing the course of the war decisively in favor of the Allies. And it was probably for these reasons that many publishers to whom Orwell submitted his manuscript shied away from circulating such a blatantly anti-Stalinist story. T.S. Eliot, for example, rejected the manuscript on behalf of the publisher Faber & Faber, and he wrote to Orwell on July 13, 1944:

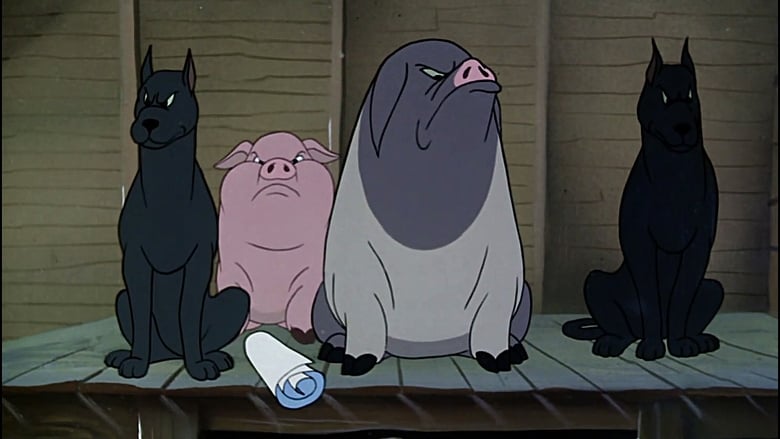

“We agree that it is a distinguished piece of writing; that the fable is very skilfully handled, and that the narrative keeps one’s interest on its own plane – and that is something very few authors have achieved since Gulliver. On the other hand, we have no conviction […] that this is the right point of view from which to criticise the political situation at the present time.[…] and your point of view, which I take to be generally Trotskyite, is not convincing […] And after all, your pigs are far more intelligent than the other animals, and therefore the best qualified to run the farm – in fact, there couldn’t have been an Animal Farm at all without them: so that what was needed, (someone might argue), was not more communism but more public-spirited pigs.”

It would take until the end of the war in 1945 for Orwell to finally find the (Trotskyist) publishers Secker & Warburg who were able to put the book on sale on August 17, 1945, a few days after the atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Now, in the midst of the general postwar debate about the future of the world and peace, Orwell’s parable was enthusiastically received and was out of print within a short time. The second edition, with ten thousand copies, was already twice as large as the first edition, and when the story soon was published in New York, it quickly became a world bestseller. The Western secret services also began to take an interest in Orwell because of his political views and his anti-totalitarian novels, and the critic George Woodcock later recalled that around 1948, “you could ask any Stalinist which British writer is the greatest danger to the Communist cause, and he would probably answer George Orwell.”

From 1950, after Orwell’s untimely death from tuberculosis, there seems to be no limit to the propagandistic exploitation of the novel: CIA agent and Paramount employee Carleton Alsop solicits the movie rights to the book from Orwell’s widow, and beginning in 1952, Western intelligence agencies led by the CIA attempt to disseminate the work throughout the Eastern Bloc from West Germany with the help of balloons. The air forces of Poland, Hungary and Czechoslovakia were ordered to shoot down these balloons and destroy any books they found. In the entire Eastern Bloc countries, this work by Orwell, just like his novel 1984, was on the list of banned books and was only available as a samizdat edition until the fall of the Wall.

After Howard Hunt, the head of the CIA’s psychological warfare division, paid U.S. producer Louis De Rochemont half a million dollars, John Halas and Joy Batchelor’s British animation studio was commissioned to make the film. In 1954, the feature-length animated picture was presented in New York at a United Nations gala and was enthusiastically received. The New York Times called it “a lively and biting animation about social revolution and disillusionment.” The film had successfully become an ideological weapon in the Cold War controversy, and it was distributed worldwide by the United States Information Agency (USIA). Reportedly, it was able to fulfill its propaganda function particularly well in Arab countries; at least, an Egyptian embassy official explained the film’s suitability to the Guardian by saying “that both pigs and dogs are unclean animals to Muslims.”

Moreover, the propaganda battle was not limited to books and films: As the relevant documents gradually became declassified and accessible at the end of the 20th century, it became apparent that Britain’s MI5 had funded comic books based on Orwell’s text that had been distributed in Brazil, Burma, Eritrea, India, Mexico, Thailand, and Venezuela. In the heyday of the Cold War, then, the film adaptation was only one aspect, albeit a significant one, of the West’s ideological and cultural offensive. But in order to achieve this goal, Orwell’s original had to be changed, and the film was given a happy ending that was not at all Orwellian: Orwell’s novel ends on an extremely pessimistic note, and he describes the pigs in such a way that they become indistinguishable from their exploitative others, the humans. The secret service-financed film, on the other hand, has a more positive ending, in which the animals ultimately receive help from other farms to successfully overthrow the animal dictatorship.

Literature

Roger Manvell, The Animated Film with Pictures from the Film “Animal Farm” by Halas & Batchelor, London: Sylvan Press 1954.

Frances Stonor Saunders, Who Paid the Piper? The CIA and the Cultural Cold War, London: Granta 1999.

Tony Shaw, British Cinema and the Cold War: The State, Propaganda and the Consensus, Tauris: 2006.

T.S. Eliot, Letter from July 13, 1944.

Daniel J. Leab, Orwell Subverted. The CIA and the Filming of Animal Farm, Pennsylvania State University Press 2007.

George Orwell, Why I Write (1947).