Christoph Huber

What can the neglected parts of Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s œuvre – his radio plays and his theater films made for television – tell us about his work?

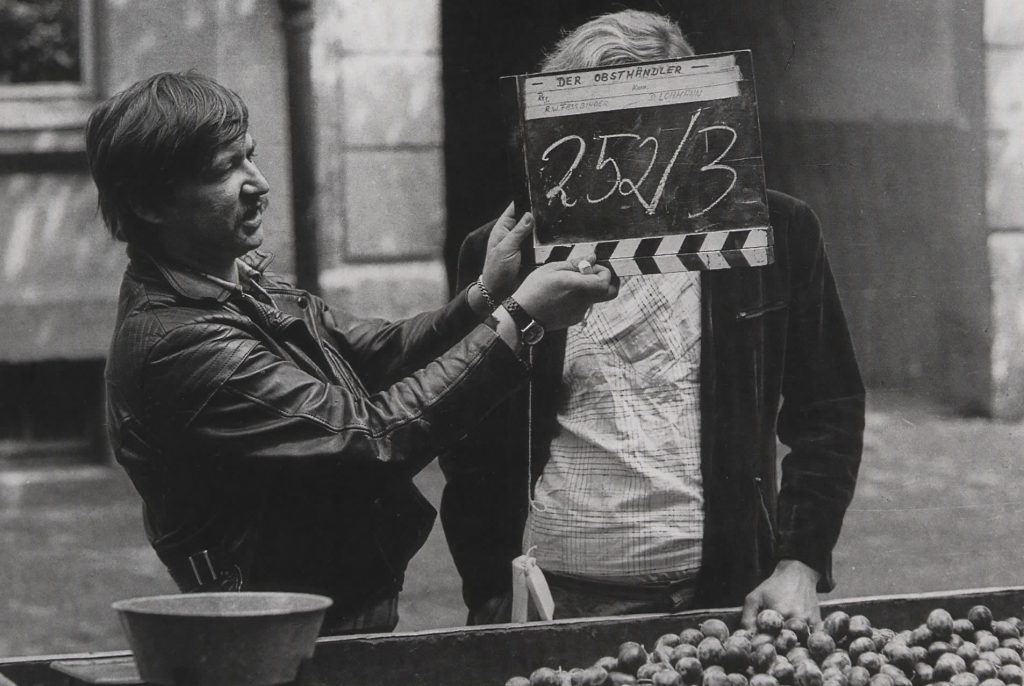

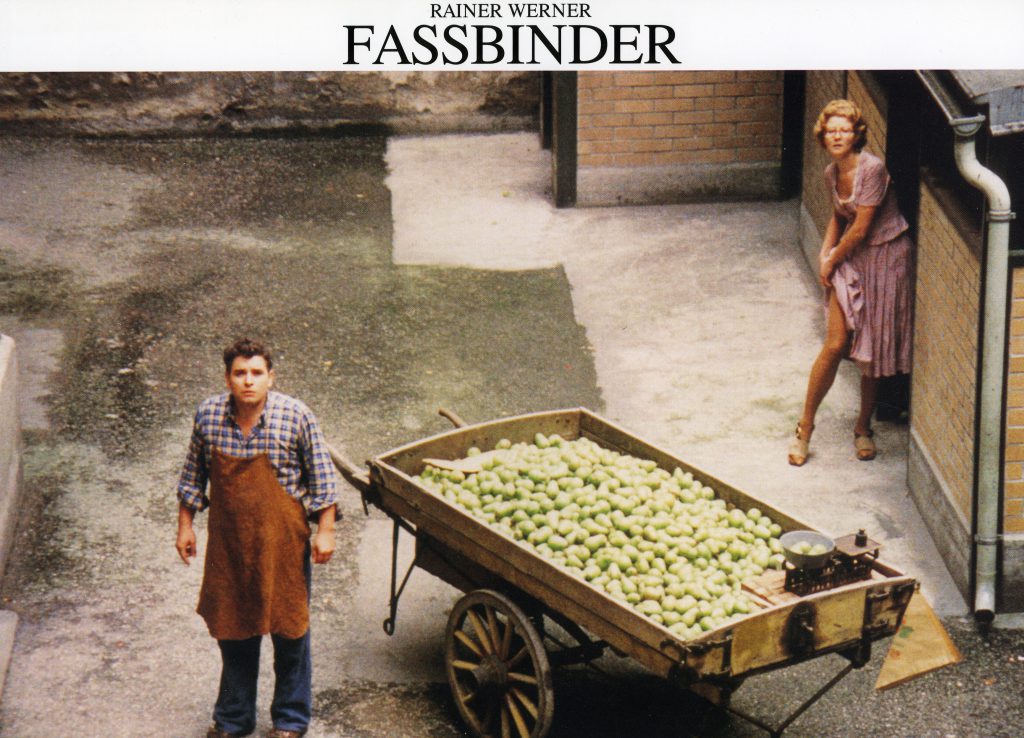

Fassbinder’s response to a questionnaire sent out by schoolchildren: “How do you imagine your twilight years?” – “I don’t count on ever getting there.” Fassbinder forever. Or so they still say. Despite current trends towards forgetfulness, there is still no way past Rainer Werner Fassbinder and his legendary persona: one-man motor of the German New Wave, internationally influential independent (then and now), his iconic appearance, the myth (genius/sadist/addict/artist/enfant terrible, and so on… take your pick), the canonized masterpieces (Ali: Fear Eats the Soul, The Marriage of Maria Braun, and so on…), sensational rediscoveries (most recently: Eight Hours Don’t Make a Day), more books (whether tell-all or academic), more exhibitions, more film series… An epic legacy of more than 40 features made in less than 15 years. But what is this idea of Fassbinder exactly? Is it merely a legend (surrounding both life and work, which he treated as basically indistinguishable), printed and reprinted until it has become Fordian fact? Is it defined by the famous films that have always stayed in circulation, thus serving as window dressing for the idea of Fassbinder? (Incidentally, this is the definition of the ubiquitous mechanism behind the popular idea of film history.) Or is it the whole shebang, down to the most obscure shorts and projects? After all, the manic tempo of Fassbinder’s output suggests that it is not about singular films – he thought of his work as “a house built from my films. Some are the cellar, others the walls, and still others the windows…” – and his astonishing prolificness is always cited as one of the first things when talking about his achievements… Which brings us back to the myth: the workaholic who burnt himself out. Anyway, I won’t pretend to unravel this Fassbinder question on this blog. But even as sizeable chunks of Fassbinder’s work are easily accessible (and thus retain a certain mainstream presence in our increasingly access-defined culture), his work is full of many dark corners and shady pits. Sometimes they’re hidden in otherwise well-known films, but they’re mostly found in stuff circulating only on the fringes, if at all. So I set out to plow some of the more neglected categories of his œuvre – Fassbinder’s radio plays and the video recordings of his theater pieces made for television, the latter ripe for rediscovery in our current Fassbinder retrospective – to see how and where they fit into Fassbinder’s “film house” and found myself amply rewarded. Which is not to say that all I found was the essence of greatness, but that these pieces offer fascinating glimpses into Fassbinder’s aesthetics and development. Let’s start with one of the radio plays, which are the most obscure Fassbinderania – actually, I only managed to track down half of them: Ganz in Weiß (1970) and Keiner ist böse und keiner ist gut (1972). Both of them are original projects, whereas Fassbinder’s other two radio plays – Preparadise sorry now (1970) and a 30-minute version of Goethe’s Iphigenia in Tauris (1971) – were refashioned from the stage versions directed during his antiteater beginnings in Munich. Fassbinder later always treated his breakthrough theater work as nothing more than a necessary step towards setting foot in the world of cinema, which is where he really wanted to go. That is certainly true, but “theatrical” ideas would keep a firm grip on his filmic output up to the very end. Even his radio plays testify to this sensibility, as their skillful arrangement of alternately interlocking and contradictory voices and sounds is shaped by stage experience that more often than not sought to express a world ruled by communication breakdown.

Another of Fassbinder’s responses to the schoolchildren’s questionnaire: “Do you consider mentally ill people a burden on our society?” – “Nobody can exist in our society without being mentally ill.” Ganz in Weiß, named after a famous (and gorgeous) schlager by Roy Black (the title translates to All in White, and the lyrics conjure up a wedding scene as a dream apotheosis of eternal love), boasts a remarkable structure: It’s a multi-layered, almost experimental collage of very short bits and pieces, something that feels quite different from Fassbinder’s cinematic approach (where comparably brief shots do appear, but mostly as ambivalent notes of grace in between long takes). However, the ingredients are recognizable, even quintessential Fassbinder. It’s the story of a boy in a protectory told by many different voices (in the form of interviews, dialogues and recollections) and defining sounds (eternally repeating orders, recurring noises of the daily grind, occasional distractions). And, of course, the music, swelling up and disappearing at regular intervals, demonstrating Fassbinder’s ear for a fine schlager, an oft-slighted form of pop music certainly capable of transcending its supposedly trivial, reassuring messages and achieving a powerful sense of all-consuming passion and ecstatic promises – or, on the other hand, descend hopelessly into the realm of the forlorn, period. What Fassbinder later achieved through the cunning use of classic schlagers in his films, from Rocco Granata’s Buona Notte in The Merchant of the Four Seasons to Lola’s Capri-Fischer Serenade, is already demonstrated in Ganz in Weiß by his hand-picked selection of more wistful gems, like Black’s Das Mädchen Carina with its very different evocation of youth, nostalgically recalling the teenage love for a circus artist, a girl “beautiful like a star in the firmament.”

By comparison, the fragmentary exploration of the life of the youthful protagonist in Ganz in Weiß contains little beauty, but much ingrained alienation. The protectory is a home of abuse and indoctrination – one of the recurring voices is that of an educator raptly evoking the discipline and glory of the Nazi epoch as an ideal to be reinvigorated – and the fleeting moments of happiness are few and far between: a transistor radio hidden away in a cigar box for nightly escape, a coin ground down so you can get it back out of the cigarette machine (one of those clearly lived-in details Fassbinder was so good at inserting into otherwise stylized contexts to give them a taste of truth). As always in Fassbinder’s work, the economic factor is emphasized as well: When the constant dream of flight culminates in an impromptu holiday in Italy, it is doomed to last only “six months, until he spent the little money he had.” This boy is clearly a predecessor of the protagonist in Fassbinder’s very personal TV film I Only Want You to Love Me. The director’s statement about Ganz in Weiß – which he saw as a meditation on “man as a result” – seems equally applicable to both films: “How can it be that someone accepts what has been made out of his life as ‘his life,’ that he is unable to develop his own fantasies, has no joys of his own, no desire?” First broadcast in October 1970, just before the short break in Fassbinder’s filmography after his first mad dash of work mania (having made ten feature films in two years, he emerged in a state of artistic crisis and needed a few months’ pause before beginning his Sirk-influenced self-reinvention with The Merchant of the Four Seasons), Ganz in Weiß consolidates certain aspects of Fassbinder’s early phase while pointing towards his more thorough, socially engaged investigations of marginalized lives. Its collage principle is something inherited from Fassbinder’s theater beginnings (Preparadise sorry now, which arranges various scenes of “everyday fascism” around stories of the killer couple Ian Brady and Mrya Hindley, would probably serve as the perfect linchpin), but the polyphony of voices relates something even more characteristic of subsequent Fassbinder films (and key to the allure of his work): Creating a sum of impressions that are curiously dazzling and ambivalent, even as the overall meaning couldn’t be made more unequivocally clear.

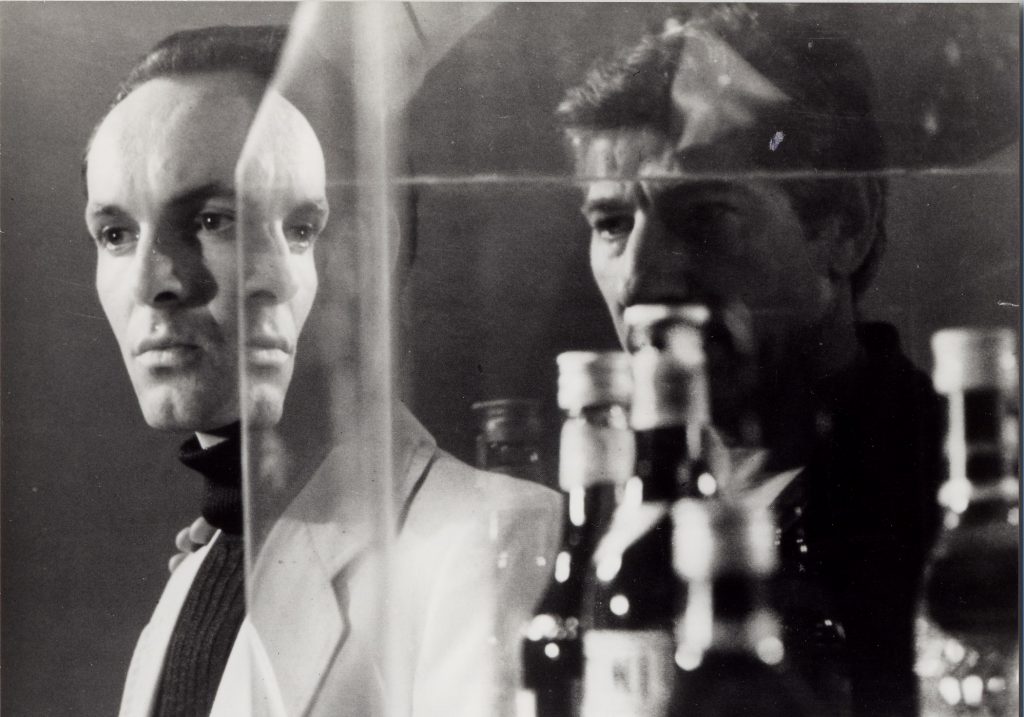

Fassbinder in an interview about his relationship to the theater: “Anyway, I never thought much of the theater. The only thing that moved me about the theater was that you could work with people in a different way. I never really had it, but I thought so: You should put yourself in situations where you can really do what I’m always dreaming of. To develop something together with others. As for myself and only for myself – meaning: others can probably do it – I’ve come to realize that I cannot do this. It was impossible in every group I was ever connected with.” In his own interpretation, Fassbinder‘s artistic crisis at the beginning of the 1970s sprang from the realization that the collaborative ideal taken over from his theater work was impossible to achieve in filmmaking. It was just a dream. For even back in the theater days Fassbinder wrested control of the productions, if we are to believe his closest companions and collaborators. So even his earliest piece of TV theater work – the first of four stage adaptations shot on video – is a fully Fassbinderean experience, and probably the most brittle thing he has ever done, making the static standstill of his early art film success Katzelmacher (based on one of his own plays) look like a Tony Scott extravaganza by comparison. Shot in black and white, Das Kaffeehaus – adapted from Carlo Goldoni’s eponymous 18th-century comedy The Coffee House – presents its spartan stage set almost exclusively from a fixed, frontal back row audience perspective. Kurt Raab remembers that even for Fassbinder’s previous stage version, which premiered in Bremen in 1969, the theater manager gave the director “full rein to whip up a Coffee House that had nothing whatsoever in common with Goldoni, instead becoming a typically Fassbinderean philosophical piece [Weltanschauungsstück], in which it’s only about the money and love is just an accessory.”

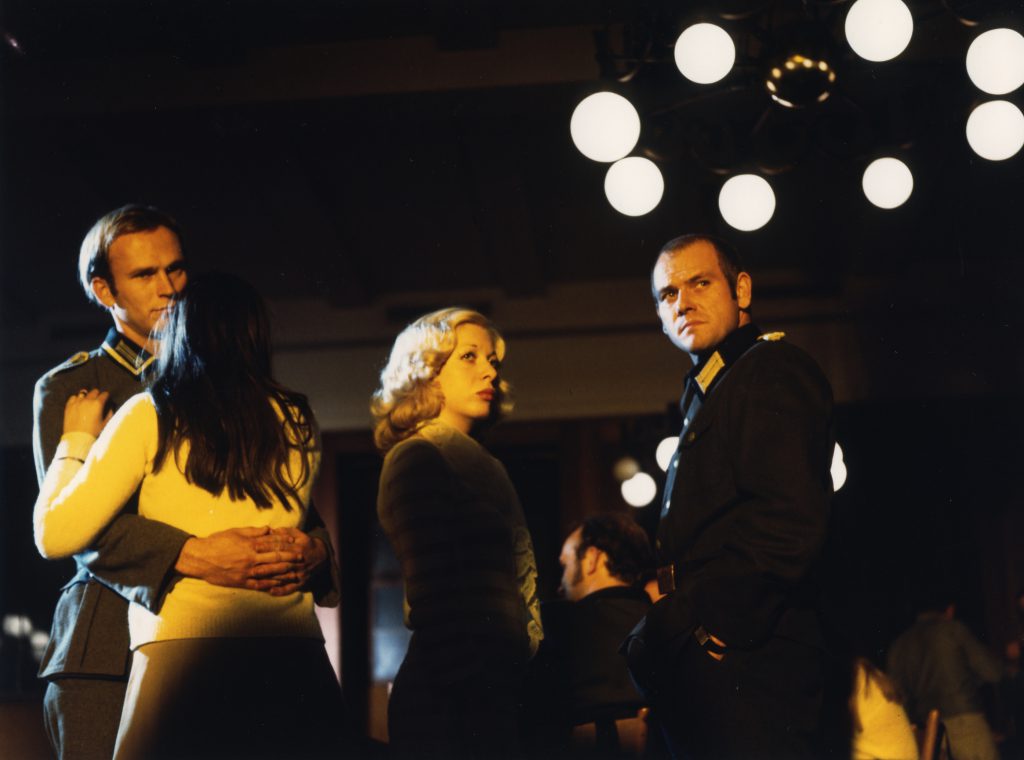

Never having seen Goldoni’s piece in another form, I’ll take the venerable actor’s word for it, since Fassbinder’s version is stridently devoid of laughter. The farcical roundelay about barter trade in business and love is stretched to tortuous lengths, in which money seems to not only be the driving force, but life force itself; while the individual vitality of the protagonists is replaced by a monotonous, mechanized idea of subjectivity, all strictly regulated by societal norms. The Coffee House may be the best approximation we have of a visual document of Fassbinder’s early theatrical endeavours. It’s also the only of his theater pieces recorded for TV made during his “pre-crisis” phase, whose last entry (though other films made before it were released later) was another adaptation of something Fassbinder had done onstage – to great acclaim. Zum Beispiel Ingoldstadt (For Instance Ingolstadt), his 1968 reworking of Pioneers in Ingolstadt (whose premiere in 1929 had been one of the great theater scandals of the Weimar Republic) for the Action-Theater in Munich, significantly contributed to the rediscovery of Bavarian author Marieluise Fleißer. A television commission shot on 35mm, Fassbinder’s Pioniere in Ingolstadt feels considerably different from the other video recordings of his theater pieces, and not just because of the look – in retrospect, it’s like a bridge towards Fassbinder’s work after his crisis break. The collapse of communication that was to remain one of Fassbinder’s major motifs began to stretch beyond the intriguing, but also very self-involved universe of the early works in a less flamboyant, but more successful manner than was the case in Fassbinder’s weirdo “Southern Gothic” western Whity. Notably, Pioneers in Ingolstadt foregrounds the female perspective (even though as much time is devoted to the futile endeavors of male soldiers), placing what little hope is left in the women.

Fassbinder interviewed about the oft-repeated accusation of being a misogynist: “Where does this misogynist idea come from? This is how I make sense of it: It’s because I am more serious about women than directors usually are. For me, women are not just there to get men started, they do not function as an object. In general, this is a cinematic stance that I despise. I show that women – much more so than men – are forced to resort to means that are at times disgusting so they can escape having to function as an object.” Fassbinder’s next video theater piece made for TV was based on his own play Bremen Freedom (Bremer Freiheit premiered on stage in December 1971, the television broadcast following exactly one year later), which carries the subtitle Frau Geesche Gottfried – Ein bürgerliches Trauerspiel (Mrs. Geesche Gottffried – A Bourgeois Tragedy). Based on a true case of the eponymous woman, a seemingly respectable citizen even nicknamed “the angel of Bremen” before being convicted for 15 murders. She’d poisoned parents, kids, husbands and others and was the last person to be publicly executed in the city in 1831. Fassbinder’s piece gives little heed to the misdeeds or the punishment, instead focusing on the circumstances that drove the protagonist to kill.

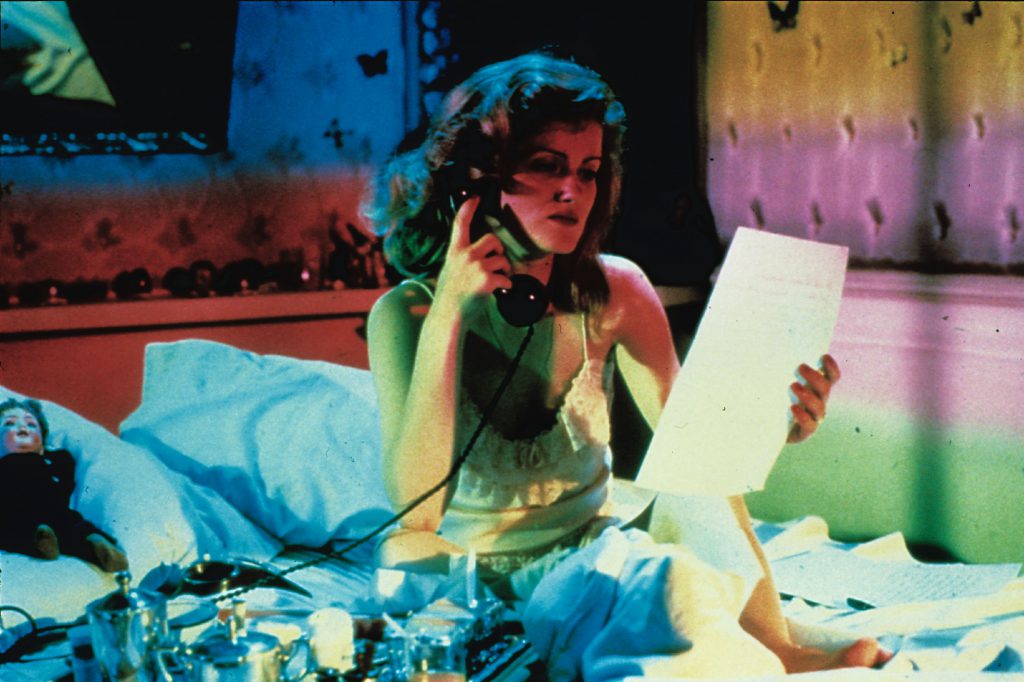

The picture-sheetlike succession of discrete scenes has something of a murder ballad to it: The opening shows Geesche treated like a slave by her soon-to-be-dispatched first husband. But content-wise Fassbinder goes for a case study and keeps the aesthetics nearly abstract. Again, the set consists of just a few scattered pieces of furniture, the real keeper being a big video wall, which serves as background surface for projected nature views and close-ups of the female lead (Fassbinder regular Margit Carstensen – “whom Fassbinder not only dedicated the piece to, he tailor-made it for her. So the superbadslim could finally give in to her unceasing urge for showing off and indulge in incomparable step-dances,” per Kurt Raab’s proudly grudging description – it’s also a kind of inverse forerunner to Fassbinder’s Martha, in which Carstensen’s suffering spouse is rendered increasingly immobile). While the overall mise en scène – by now Fassbinder makes pointed use of montage – is not as stridently minimalist and distancing as in The Coffee House, Bremen Freedom somehow manages to up the ante on alienation, mainly because the huge disembodied video projections add to the feeling of being stranded in an uncomprehending world: a ghost in the machine. Surely the height of innovation at its time – Fassbinder and his DP Dietrich Lohmann basically decided to simply try out the possibilities of early electronic cameras and a blue box, then went for it all the way – for a latecomer like me this theater video evokes strong memories of the artsy-fartsy video experimentation ubiquitous in 1980s television, adding to the feeling of displacement. And yet it doesn’t feel pretentious: Fassbinder clearly envisioned a mirroring effect of style and subject.

Fassbinder interviewed about his plans for staging an opera (which never happened): “But – as with theatre – I don’t want to do what has already been done, I want to create something new. Like in theater: I’ll only do theater again when you can work as in cinema: in a manner that is concrete, direct, together with people who are interested in it and affected by it. Just reading plays and then saying: ‘We want to do this piece now,’ I don’t do that anymore, at all, that’s what I’ve actually decided.” Next, Fassbinder’s controversial Ibsen adaptation Nora Helmer (1973) continued in the same thematic vein, but – in tandem with Fassbinder’s cinematic development – unleashed the camera to freely prowl through an elaborate set. Ibsen’s doll house became a von Sternbergian manor whose ornate decor consistently conjures up luxurious confinement. A proverbial golden cage in which the finely woven curtains and opulent architecture seem like nets and grids ensnaring the protagonists. An extra touch of Fassbinderian perversity is added by the flat video image, which yields results antithetical to the sumptuous stylization. Surrounded by some of Fassbinder’s most artificial films like The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant and his camera-pirouetting masterpiece of mannerist excess, Chinese Roulette, Nora Helmer is an important step on the path towards the latter, which Fassbinder described as follows: “I tried to make a film that carries artificiality and art form to the extreme only to place them in question afterwards.”

Like Chinese Roulette, Nora Helmer is also quite literally a work of reflection, with an abundance of strategically placed mirrors – though in the end the reflection is left to the audience, whereas the characters fail once more. To quote Fassbinder on his movie’s goals again: “To me, rituals continue in the mirrors and are refracted by them, and I hope that these refractions enter the subconscious of the viewer so he will be ready to break with these rituals, the terminal point of a bourgeois way of life.” Like the protagonists of Chinese Roulette, his Nora remains trapped at this terminal point (as opposed to Ibsen’s original play, where she leaves in the end), which drew a lot of flak for turning a proto-feminist piece into an anti-feminist statement. Yet this exemplifies one of Fassbinder’s enduring, if at first glance occasionally vexing strategies: His perverse, but pointed evocations of every form of relationship as a double bind in which the power structures are never one-sided (every victim is also a perpetrator and vice versa). Picking up on Bremen Freedom, which he characterized as “an emancipatory play that is also against emancipation as it is practiced these days,” he saw his Ibsen interpretation “as a piece in which everybody, Nora included, would have to emancipate themselves.” That’s Fassbinder’s utopia: He always hoped the viewer would manage to learn from his warped didactic dramas.

Fassbinder interviewed about his Ibsen adaptation: “We didn’t change anything, just shortened – a lot of text. In our version, Nora doesn’t leave in the end. She stays, because there are ten thousand families with the same quarrels that Nora and Helmer have, and usually the woman doesn’t leave. After all, where should she go? That’s why people always find some way to make an arrangement, which is fundamentally worse. One has to criticize this kind of arrangement instead of merely claiming separation is possible, because it is in fact not an option.” Although it doesn’t feel as radical as Bremen Freedom and Nora Helmer, Fassbinder’s final theater adaptation Women in New York (1977) – originally shot on 16mm – can be seen as a culmination point of his theatrical TV experiments. A presumably faithful rendering of his 1976 Hamburg stage production Frauen in New York, it also closes the circle: Just like The Coffee House, it takes what originated as a comedy and diligently proceeds to make it stridently unfunny. For cinephiles, the perverse fascination is heightened by the fact that there are readily comparable “straight” adaptations of Claire Booth Luce’s original play, a satire about infidelity and social networks, most notably George Cukor’s eponymous star-studded screwball classic The Women (1939). If Cukor’s glamorous MGM version qualifies as a bona fide camp classic full of bitchy repartees and conniving schemes, in Fassbinder the all-female cast (whose every word and act is governed by the absent men) becomes a cross section of structurally repressed power. Their double-crossing and indirect violence become an expression of internalized repression, the sexism and inequality inherent in bourgeois society subconsciously imprinted on the psyche of the women. Fassbinder encourages his actresses to channel the dilemma into hard-to-take hysterics, their socialite power struggles contained in a handful of stylized sets with a distinctly Fassbinderean look, like a potentialization of Petra von Kant. Fassbinder returned to theater for the intriguing documentary Theater in Trance, but that is something else. He seemed to have found an endpoint of negativity.

Fassbinder’s response given in an interview, answering the question whether the “positive realm” exists for him: “It does not. I think that the social order I live in is not defined by happiness and freedom, but rather by repression, fear and guilt. In my opinion, what we are taught to experience as happiness is a pretext that a society ruled by coercion offers the individual. And I do not accept this offer.” Yet, in a text written about his Nabokov adaptation Despair, released the year after Women in New York, Fassbinder does offer an idea of the positive realm: “Our relationships are cruel games with each other because we do not accept our end as something positive. It is positive because it is real. The end is the tangible life.” Fassbinder obsessed about the subject of death in interviews, stressing how liberating it was for him to accept the fact of his own death after an incident in the early 1970s. Many of his protagonists are driven by a death wish, but he never tackled the subject of the ending as heads-on as in his last radio play, Keiner ist böse und keiner ist gut, the title itself a Fassbinder statement if there ever was one: Nobody Is Evil and Nobody Is Good. Subtitled Ein Versuch über Science Fiction (An Experiment About Science Fiction), it shows him approaching the genre in an even more oblique way than his TV two-parter World On a Wire the following year. World On a Wire languished in obscurity for a long time after its 1973 broadcast, but has been triumphantly resuscitated in the new millennium as a major work of speculative fiction: Its corporate thriller plot and simulated reality speculations serve as a basis for a Fassbinder meditation on sensation and perception (it is also one of his most mirror-obsessed works). Even more radical, Nobody Is Evil and Nobody Is Good barely has a plot, but rather establishes a situation: People have dreamt of the impending end, which is envisioned as an overwhelming, kaleidoscopic event of wonderful colors and harmony: “We will all be part of it.” Centered on a family of five (parents, children and grandfather), the radio play establishes its premise via an accidental, mysterious (but not threatening) late-night telephone call proving the dream of the joyful apocalypse has spread worldwide: “I don’t speak this language, Petrov, but I understood him,” the wife reassures her husband. There are a few minor complications, but even those cause only mild unrest as the various voices drift towards the utopian release from society’s terrors and necessities promised by oblivion: The family is unsettled because grandfather “did not have the dream […] he should have been prepared,” but it turns out that he will die from natural causes before the event. “There are no mistakes,” one states calmly, while another notes: “I liked grandfather, but I cannot remember it anymore.” This may be the only Fassbinder piece fully founded on acceptance rather than resistance, doubt and despair, the backside of his subversive strategies. For 30 minutes, people quietly reassure each other and are able to forget all their differences (the titular sentence is embedded among similar statements like “everybody is right and everybody is wrong.” Just before the end, the son calmly states: “We are happy for the very first time.” Fassbinder himself reads the (small) part of the narrator, describing the long-awaited end: “As everything died, as everything turned to color and happiness, there was a momentary confusion in space. But immediately what existed joined the existing and became beginning.”

Fassbinder announcing a (never-realized) play about the end in his text on Despair: “That’s the topic of my new piece. It’s called ‘End Endless.’ Destruction is not its own opposite when that term no longer exists, has become meaningless, when it possesses a reality that makes it disappear. It would be exciting to see what people would come up with then.”