Anupma Shanker

Nearly half a century has passed since the first Black British feature film Pressure directed by the Trinidadian-British filmmaker Horace Ové was released in 1976. And yet, the phrase ‘Pioneers of Black British Cinema’ is likely to stir up a degree of genuine blankness, surprise or plain intrigue amongst most audiences worldwide, including in Britain. And understandably so. History reminds us that far too often, speaking truth to power hasn’t gone well for artists worldwide. Black British filmmakers have not been an exception to this rule, having paid a hefty price for their audacious on-screen expressions of protest against racism, injustice and oppression, thus existing merely as what film critic and curator Ashley Clark calls, “a ghost canon of British filmmaking … urgent work that has often been overlooked, actively suppressed, or left to languish in the margins, unloved or inaccessible.” “Pioneers of Black British Cinema” is an attempt to bring to light some of the early groundbreaking works of British filmmakers and artists of African-Caribbean heritage belonging to this “ghost canon.” Spanning across three decades between 1970s and 1990s, and often described as “incendiary,” “controversial,” “angry,” and “nihilistic,” the five features and three shorts that form part of the programme are not only powerful reflections of pivotal moments in race-relations in Britain but also serve as a unique cultural archive of the Afro-Caribbean communities that came to post-WWII Britain from the Commonwealth (territories of the British Empire) in search of a better life.

COMMONWEALTH MIGRANTS AND THE MAKING OF POST-COLONIAL BRITAIN

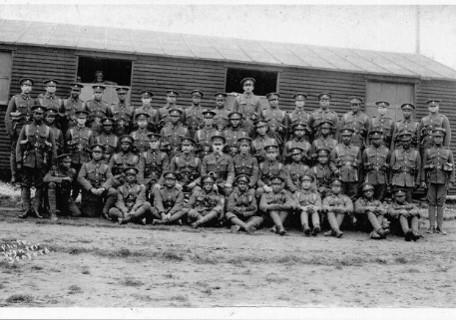

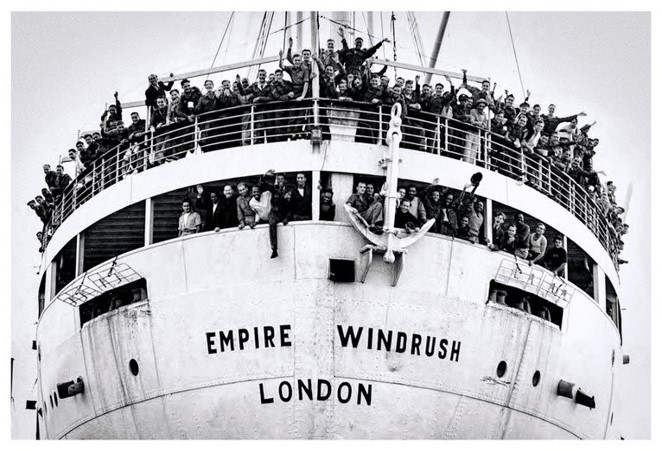

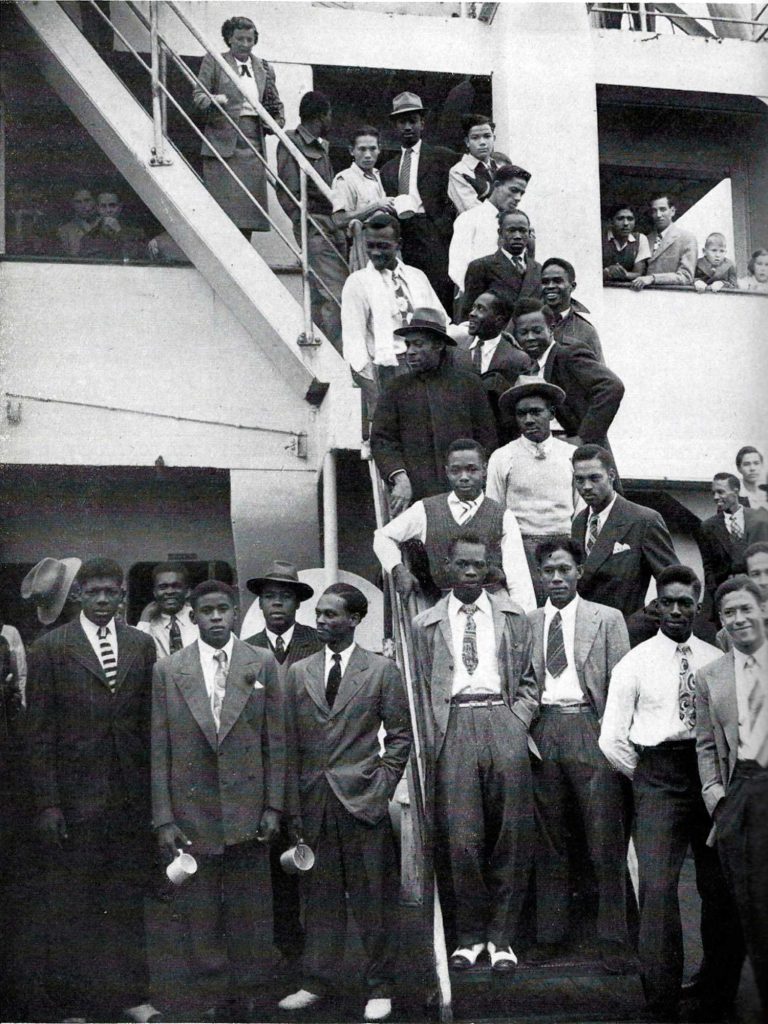

From a historical standpoint, the presence of Black communities in Britain can be traced as far back as the 1500s, with official figures confirming that up to 20,000 black people were known to live in the United Kingdom in the 1760s (including up to 15,000 in London). After Britain joined the First World War, over 3 million people from across the British Empire and Commonwealth, including nearly 180,000 Africans and 15,000 West Indians served in the British Army. Between 1939 and 1945, the British army recruited nearly 600,000 black men and women who served in various military branches to defeat the Nazis. After the war, Britain was faced with acute labour shortages and once again its colonial subjects from India, Africa and The Caribbean were summoned to rebuild the country. The arrival of HMT Empire Windrush on 22 June 1948, the iconic passenger ship that brought 1027 hopeful Jamaicans to England on British government’s invitation to come and “help the mother country,” marked a watershed moment in immigration in post-colonial Britain.

Many of the Black British artists and intellectuals whose works are featured in the programme such as Horace Ové, Sam Selvon, Menelik Shabazz, Isaac Julien, Dennis Bovell, and Brinsley Forde are amongst those who either belonged or descended from the ‘Windrush Generation’ (a term used for British Caribbean people who migrated to the UK after WWII), and whose artistic expressions reflect their own lived-in experiences as well as the collective struggles of fellow West Indians trying to integrate in a racially and culturally hostile Britain grappling with the demise of its vast global empire.

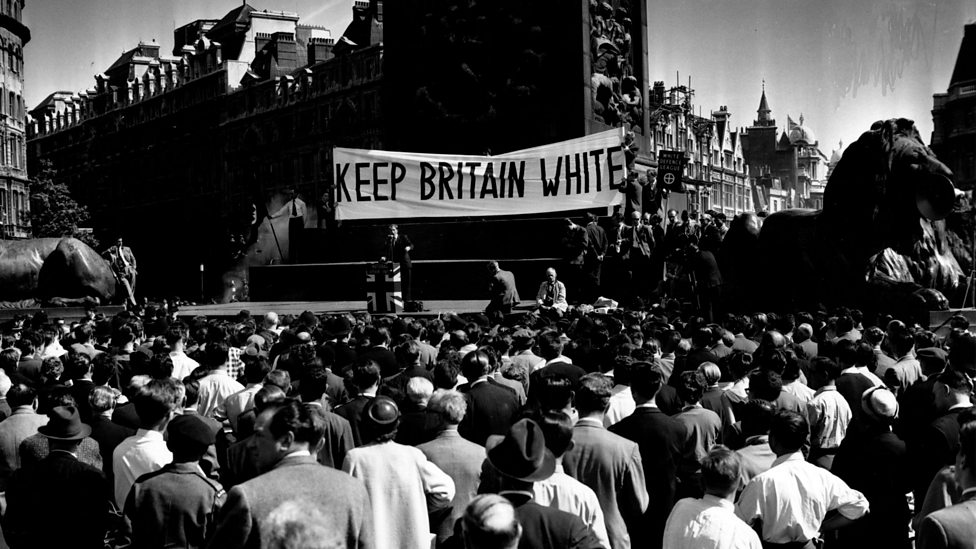

With many British colonies gaining independence during the 1950s and ’60s (beginning with India in 1947), immigration from Africa, The Caribbean and South Asia peaked during the 1960s and 1970s causing anxiety and xenophobia amongst white Britons who saw “coloured people” (Blacks and Asians) as a threat to their way of life and livelihood. Exacerbated by record unemployment, economic decline and white nationalism fuelled by far-right groups such as National Front, the years that followed were rife with racial and civil unrest. Extremist subculture groups such as Teddy Boys (implicated in the 1958 Notting Hill race riots) and White Power Skinheads marched on the streets with Nazi symbols & racist slogans such as ‘Keep Britain White,’ and frequently launching unprovoked attacks on Black and South-Asian communities. The flames of racial and cultural division were fanned further by Conservative politician Enoch Powell who in his 1968 infamous speech titled ‘Rivers of Blood’ stated that, “In this country in 15 or 20 years’ time, the black man will have the whip hand over the white man.”

CAN’T TEK NO MORE: REGGAE, RESISTANCE AND THE FORMING OF BLACK-BRITISH IDENTITY

Despite the passing of Race Relations Acts in 1965 and 1968 which made racial discrimination illegal in Britain, hostility and violence against Black and Asian immigrants continued to rise, leading to several nationwide race riots. In addition to defending themselves against xenophobic attacks from far right groups and individuals, Black and Asian inhabitants found themselves locked in recurring conflicts with the police unleashing a pattern of discord, rioting and unrest that would go on to define the political and social volatility of Margaret Thatcher’s era. Tired of being constantly cited as the ‘problem’ and seeing no recourse to their travails, in the late 60s, various anti-racist and anti-fascist movements led by Black and Asian youth began to develop in Britain. Similar to the United States, the British Black Power Movement and British Black Panthers came to prominence in 1968, uniting Black and racial minorities under a common label of ‘Political Blackness’ in recognition of the urgent need for self-defence, self-determination, and racial pride. Their young leaders sought to create safe spaces where Black and Asian communities could nurture and advance their political & cultural interests. ‘Rock Against Racism,’ a musical campaign that saw black & white musicians join hands against xenophobia and fascism, was born in 1978.

A pivotal moment occurred in 1973, when Jamaican Reggae icon Bob Marley made his first appearance on the BBC. Marley’s arrival in Britain not just proved a turning point in his international career, it also transformed him into a prophet-like figure, empowering and inspiring the disenfranchised Black youth and Black Resistance movement through his revolutionary songs which became anthems for social and political change. Marley also introduced Britain to roots Reggae – a hypnotic Jamaican sound that went on to rewire the British music industry, and instilled a sense of cultural and ancestral pride amongst up-and-coming Black British musicians like Brinsley Forde (frontman and founder of the renowned British Reggae band ASWAD). Forde appeared as the young Rastafarian DJ Blue in the landmark Black British film Babylon (1980), embodying the ethos of Reggae and Jamaican Sound System culture while battling racism and police brutality in the 1980s London.

ON-SCREEN REPRESENTATION OF BLACK BRITISH EXPERIENCES

While disenfranchised Black Britons continued to fight for survival, the issues concerning their manifold struggles remained hidden from film, television and public discourse, with the only ‘representation’ of Black youth emerging through predisposed narratives of the British news media, as articulated by British filmmaker and artist John Akomfrah: “I think everyone my age, who came of age in the 1970s had this adventure with what I call the ‘doppelgänger,’ the double. There was this talk in society about the figure called ‘the black youth,’ and this black youth was a criminal, mugging, fearful creature. You heard about this figure, but you didn’t think that it had anything to do with you, and then … there’s a mirror moment when you suddenly realize: fuck, they’re talking about me! … It was like, oh well, since I am supposed to be this creature, I’d better get to know it, I’d better become it, and learn how to get it to speak in the way that I want to speak.” (Source: ashleyclark.substack.com).

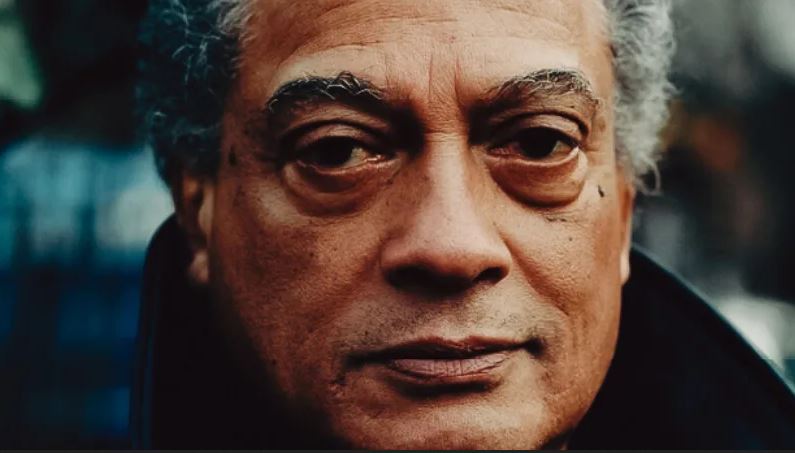

It wasn’t until the 1960s, when a palpable shift in the attitudes of the British film and television industry allowed for an increasing number of artists of African-Caribbean heritage to step forward and articulate their own stories, leading to some of the early documents of Black British Protest Cinema. Oscillating between rage, racism, reggae, and resistance, the memories and recollections of their inter-generational experiences very much constitute the cultural and spiritual DNA of this film movement. At the helm of this artistic and intellectual outburst was Trinidadian-British director Horace Ové, whose hard-hitting debut feature Pressure (1976) became the first Black-British film to chronicle the anxieties and identity struggles of the Windrush families in the 1970s Britain. Co-scripted by fellow Trinidadian writer Sam Selvon (author of the 1956 seminal novel The Lonely Londoners), the film’s gritty narrative shines light on the experiences of a Trinidadian family as they seek acceptance and assimilation within a palpably racist British society. Ové, who had come to Britain from Trinidad in 1960 to study painting, photography, and interior design knew what it was like to “live in two worlds” (as he once said in an interview). As a photographer, he chronicled major figures of the Black Power movement such as Michael X and Stokely Carmichael. His prolific and often controversial career which spanned over five decades, included a number of compelling documentaries such as Baldwin’s Nigger (1968) featuring the African-American writer James Baldwin, and Who Shall We Tell? (1985), a powerful account of the Bhopal gas tragedy in India.

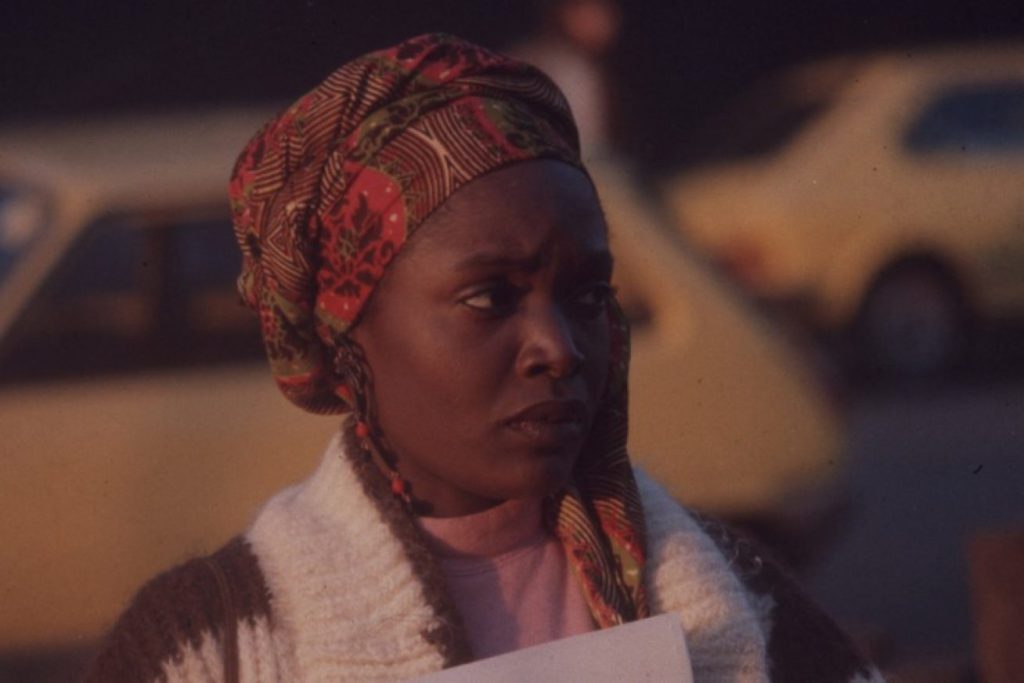

Ové paved the way for the Barbados-born filmmaker, producer, educator and writer Menelik Shabazz, a trailblazer of independent Black British filmmaking whose long and enduring career includes seminal filmic accounts of Black British history such as Blood Ah Go Run (1981), Catch A Fire (1996), The Story of Lovers Rock (2011) and Looking for Love (2015). Shabazz’s landmark debut feature Burning an Illusion (1981) traces a young Black woman’s journey to self-awakening and emancipation, and is considered a milestone of Black British cinema. In 1984, Shabazz formed ‘Ceddo Film and Video Workshop’ with a group of fellow Black British independent filmmakers with the vision “to empower black film production, training and film screenings.” Ceddo went on to produce a number of ground-breaking documentaries, including Street Warriors (1985) and Omega Rising – Women of Rastafari (1988) – a first-of-its-kind documentary by the self-taught camerawoman and Rastafarian poet Elmina Davis that gave voice to the women of Rastafari and explored their relationship to the movement.

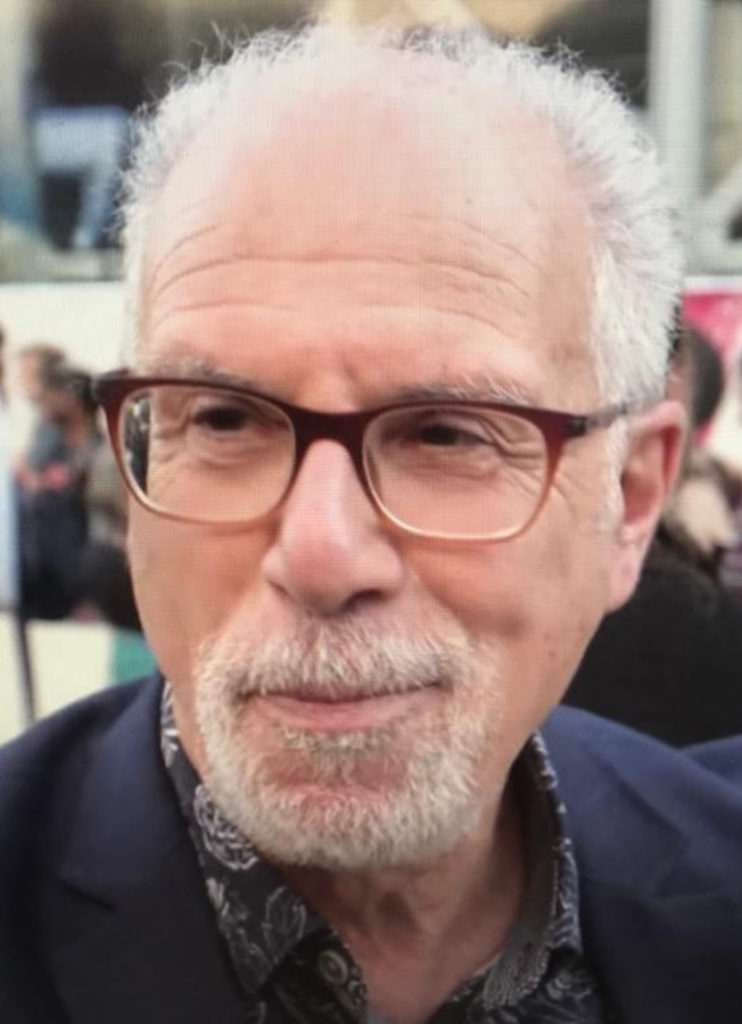

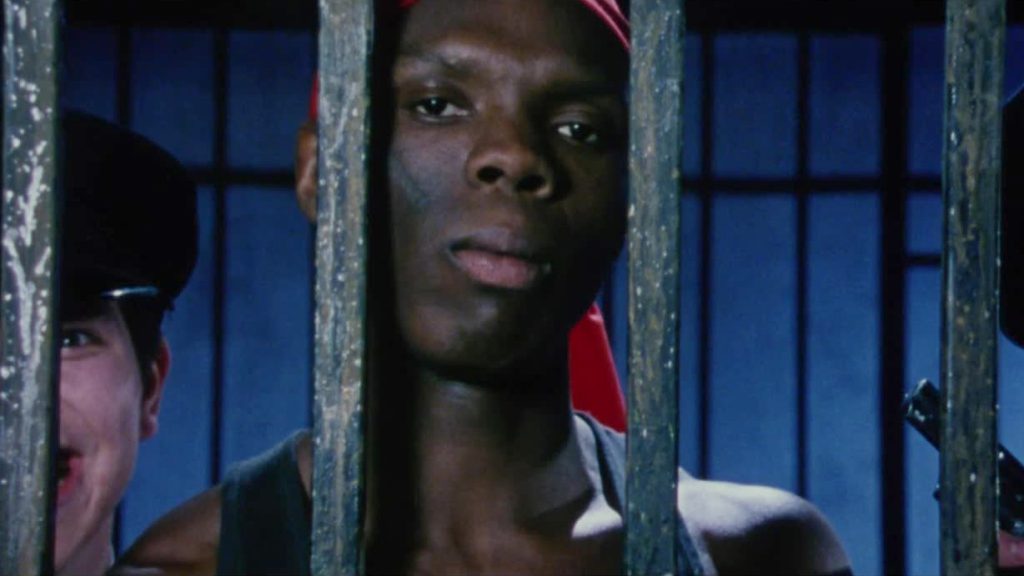

An exception to the group was the Italian-born British director, writer and editor Franco Rosso, whose personal experiences of post-war xenophobia turned him into a fearless voice of the marginalized. Rosso directed a number of controversial black-orientated documentaries, including The Mangrove Nine (1973) about a group of British black activists falsely tried for inciting a riot, and Dread Beat And Blood (1979) featuring Jamaica-born, British-based Dub poet and political activist Linton Kwesi Johnson. His debut feature Babylon (1980), an incendiary portrait of Reggae, racism and police brutality in 1980s London is set against the backdrop of a newly-installed Thatcher government and is hailed as a cult-classic of Black British cinema. Rosso co-scripted the film with Martin Stellman who’d worked on Quadrophenia (1979), a critically-acclaimed drama about England’s Mod subculture. Despite premiering at Cannes to a near-unanimous acclaim, Babylon was rejected by the New York Film Festival for being “too controversial and likely to incite racial tension,” and it was only released in the US four decades later in 2019.

The ’80s and ’90s saw a number of boundary-pushing artists emerge from the talent pool of Black British diaspora. Prominent voices included: Ghanaian-born British artist & filmmaker John Akomfrah, Installation artist & filmmaker of Caribbean descent Isaac Julien, and British-Nigerian film director Ngozi Onwurah – all of whom continued to explore and expose the myths & realities surrounding the subject of ‘Being Black and British’ through their unique artistic practices.

John Akomfrah’s poetic ruminations on race, identity and post-colonialism over the past three decades have transformed him into one of UK’s leading contemporary filmmakers and installation artists. His oeuvre includes: Seven Songs for Malcolm X (1993), The Nine Muses (2010), The Stuart Hall Project (2013), The Unfinished Conversation (2013), and Four Nocturnes (2019). Akomfrah’s artistic journey began in 1982 when he co-founded the Black Audio Film Collective (BAFC) with fellow artists and long-term producing partners David Lawson and Lina Gopaul, as a response to the social unrest in the 1980s Britain. His first film Handsworth Songs (1986) is a profound mediation on race and civil disorder in 1980s Britain, and explores events surrounding the 1985 riots in Birmingham and London through a combination of archive footage, still photos, newsreel and newly shot material. The film premiered at Cannes and won the Grierson Award for Best Documentary. In 2024, Akomfrah represented Britain at the 60th Venice Biennale where he showcased his soundscape installation Listening All Night To The Rain (2024), an immersive exploration of the migrant experience.

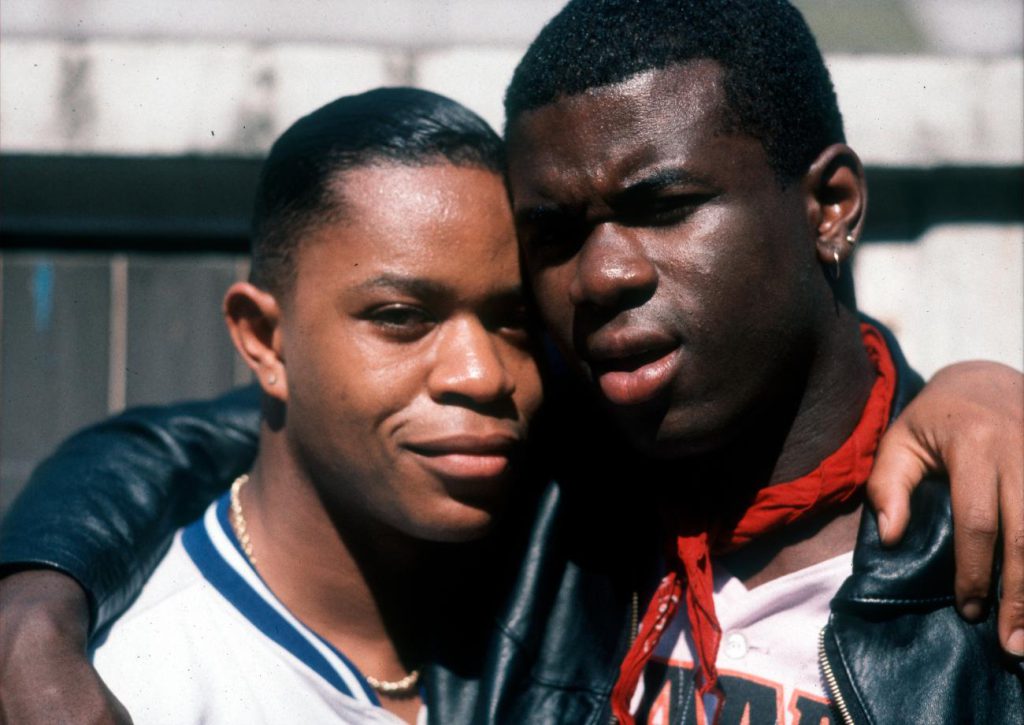

Isaac Julien’s critically acclaimed career spans across forty years and includes a long list of films and multi-screen film installations that combine different artistic disciplines to construct powerful visual narratives. Like Akomfrah, Julien formed the Sankofa Film and Video Collective (SFVC) with fellow Black artists like Maureen Blackwood and Nadine Marsh-Edwards in 1983 with the aim of, “developing an independent black film culture in the areas of production, exhibition and audience.” He received widespread acclaim for his 1989 film Looking for Langston, a rumination on the American poet and social activist Langston Hughes and the Harlem Renaissance, from gay black perspective. His bold & stylish debut feature Young Soul Rebels (1991) raises the questions of sexuality, gender, and national identity against the rise of various youth subculture movements in the 1970s London. The film won the 1991 Critics Week Prize at Cannes and is considered a landmark of Black British Queer cinema.

Akomfrah and Julien inspired subsequent generations of Black British filmmakers like Ngozi Onwurah (who graduated from the same art school as Julien). The first Black British woman to have a feature film released theatrically in the UK, Onwurah’s unique perspective on Black Cinema and the politics surrounding it is very much shaped by her own mixed-race heritage. Her multi-award winning short (also her graduation film) Coffee Coloured Children (1988) is an intimate experimental monologue about the trauma of racial harassment and self-hate that she and her brother Simon (the film’s producer) endured growing up as biracial children in Britain. In Flight of the Swan (1993), a young black ballerina rejects racial prejudice and re-connects with her African inner spirit in Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake. Onwurah’s debut and solo feature to date, Welcome II The Terrordome (1994) borrows its title from the 1989 track by New York rappers Public Enemy, and is an experimental dystopian thriller that envisions an anarchic, futuristic Britain suffering the consequences of its colonial past. A low budget affair with predominantly black cast, Onwurah’s ‘angry film’ (as she refers to it) was shunned by critics upon release for its nihilistic view of race relations in Britain. 25 years later, it appears more relevant than ever as much of what was perceived as excessive or sensational by critics back then – police atrocity, links between slavery and systemic racism, inequity – sadly isn’t so shocking or dismissible today.

THE AESTHETIC, NARRATIVE AND CULTURAL LEGACY OF BLACK BRITISH CINEMA

As a marginalized film movement that is rooted in the intersectionality of race, identity and post-colonialism, in many ways, Black British Cinema offer us a rare and non-traditional perspective on the political, social and cultural foundations of post-war Britain, and on the notion of ‘Britishness’ itself: one that is derived from what it possesses but also from what it has been denied, and therefore cannot/does not possess. Amongst its most treasured possessions are the authentic, uncompromising, and agonizing portraits of Black British lives it represents, and whose real and portrayed experiences are terrifyingly undistinguishable. In terms of what it has been denied-lavish budgets, fancy locations, famed cast and crew, accolades – these absences only serve as a stark reminder of the politics of race relations in Britain at the time, and its punitive consequences on marginalized artists and their sympathizers. Notwithstanding these material paucities, the austere aesthetic of this canon neither dissuades from accessing their spiritual essence, nor does it deter its authors from baring the souls and scars of their people on screen. On the contrary, in engaging with these gritty images of a time, space and community unseen, unheard and therefore deemed to un-exist for anyone other than themselves, one experiences a distinct film tradition that fuses the European realism of filmmakers like De Sica, Fellini and Ousmane Sembène (which influenced Horace Ové) with authentic expressions of its Afro-Caribbean creators, and seeks to alchemize the collective rage and resistance of its people into timeless art, while also serving as a valuable archive of Black British history.

From a film appreciation perspective, quite often words like ‘pioneer’ and ‘groundbreaking’ are used to affirm the true worth of a filmic endeavour, thus moulding public expectations in specific terms. However, in case of Black British cinema, their true merit cannot be assessed or established through traditional parameters applied to their non-Black counterparts (star cast, budget, location, technique, awards etc.), rather in reminding ourselves that the truly groundbreaking and/or pioneering aspect of these cinematic documents and their creators lies in the sole fact that against all odds (that one could possibly imagine), they’ve somehow dreamt, dared, and managed to exist. And it is by continuing to exist that they are able to show and tell us-frame by frame – of the many ground(s) they each were forced to break in order to make it thus far, and of many other grounds that remain to be broken with regards to the issues of race, identity, immigration and post-colonial attitudes in Britain and elsewhere today, particularly at a time when, to borrow from Shakespeare, to be or not to be (black, brown, migrant, refugee and so on) is sadly still the question, both an existential and spiritual one.

Anupma Shanker is a film curator and audio-visual archives researcher

November 6 to 27, 2024 at the Austrian Film Museum: Rage, Racism, Reggae, Resistance: Pioneers of Black British Cinema

Image Sources

[2] Blackhistorymonth.org.uk; [3], [9] Bbc.co.uk; [4] Reading Museum;

[5], [6] tribunemag.co.uk; [7] libcom.org; [8] National Archives UK;

[10] Film and TV Charity UK; [12] MenelikShabazz.co.uk; [14] Theguardian.com;

[15] MartinStellman.com; [17] David Levene; [19] Royal Academy of Arts, London;

[21] blackwomendirectors.com