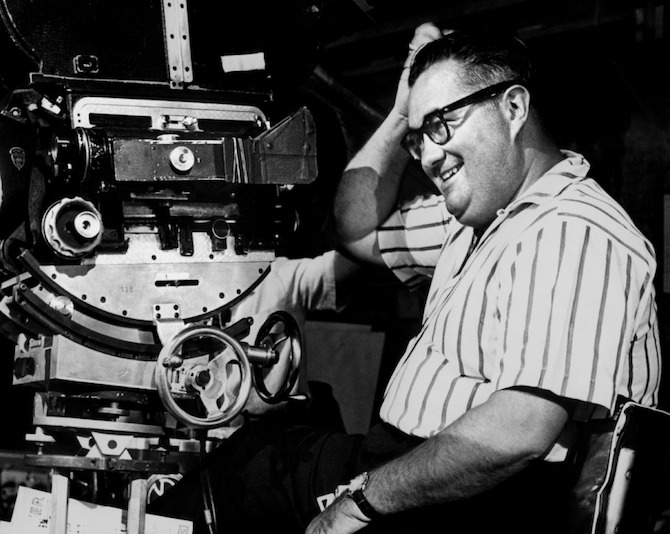

Taking our retrospective of the films of Mario Monicelli as a starting point, Christoph Huber and Patrick Holzapfel discuss the neglected history of assistant directors in cinema.

Patrick Holzapfel: Christoph, after reflecting a bit on what we could say about Mario Monicelli, we stumbled over the topic of assistant directors (AD). A topic, which has mostly been ignored in film history. Monicelli talked about it quite a lot, having worked as AD in the beginning of his cinematic career. It is an interesting profession half-way between organizational skills and the widespread desire to make films oneself one day. Yet, there are also a lot of people dedicating their life to being a AD. What I find very interesting is that no specialization, no craftsmanship is needed in order to work as a AD. But many different talents are necessary…

Christoph Huber: Exactly. We will also get back to your own experience working as a AD, but first I want to point out that the lack of discussion on the subject of AD’s is connected to something lacking in general. Namely, that film critics have far too little understanding of how a film is really made. There are only a few critics really knowledgeable about camerawork, for example, meaning: the technical aspects. The same is true concerning AD’s. They exist only as a rather abstract notion among film critics. The same goes for me, I guess: So, when you proposed this topic for debate, I started by reflecting on it from the point-of-view of auteurism. I looked up which films Monicelli had worked on as a AD at the start of his career and asked myself if we can learn something about his filmmaking from it. Coincidentally, not long ago I have seen the short film on which Monicelli had his first credit: The Tell-Tale Heart (Il cuore rivelatore, 1934), a silent Edgar Allen Poe adaptation he realized together with his friend Alberto Mondadori, who became an important literary figure. It seems Monicelli worked as something in-between co-director and AD with Mondadori and they are credited as co-writers. Yet, this had still something of a youthful amateur project—Monicelli later called it “my first cinematographic experiment”. Only afterwards, he started working professionally as AD: I wrote down five directors he worked for and thought about what that could mean in terms of influence. His earliest AD credit was for Augusto Genina. Monicelli worked on White Squadron (Lo squadrone bianco, 1936), which I finally could see at Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna last year. It’s a really fascinating, but also totally fascist desert war film, so basically the opposite of what Monicelli was doing later on! Then he worked with another relatively big name, Gustav Machatý, on Ballerine (1938), a film I haven’t seen. After that, his “major AD phase” started, continuing throughout the 1940s. The two outstanding directors Monicelli worked with during those years are Pietro Germi and Goffredo Alessandrini. Especially the former seems a good fit for Monicelli, even as the two films he worked on—The Testimony (Il testimonio, 1946) and Lost Youth (Gioventù perduta, 1948)—are crime dramas. Only later, Germi would become very successful internationally as a director of satirical comedies like Divorce Italian Style (Divorzio all’italiana, 1961), helping to establish Commedia all’italiana, which Monicelli is mostly associated with. In fact, one of Monicelli’s biggest hits, My Friends (Amici miei, 1975), was a Germi project Monicelli directed after his colleague’s untimely death: The credits even say “a film by Pietro Germi”. But mostly, as a AD, Monicelli worked a lot with typical craftsmen, not auteurs: people like Giorgio Bianchi and especially Giacomo Gentilomo. It is very hard to draw conclusions about Monicelli’s own work from most of these.

PH: You also found a great text by Volker Schlöndorff dealing with the topic.

CH: Yes, on Jean-Pierre Melville. In my opinion this piece is better than any meter of film Schlöndorff shot during his career. Yet he doesn’t write so much about his work as AD but about the influence Melville had on him. It is strange because one can hardly see that influence in his films. Maybe in Young Torless (Der junge Törless, 1966) we can still find a formal rigor reminiscent of Melville. But that’s it. The question might be asked if it is of any importance at all for whom one works as AD.

PH: I think it is also about learning what one does not want to do. And you learn about things that might be invisible in the finished films. Like how to—and how not to! —address the people working on a film set and so on. Then again, I am not so sure these things really are invisible in the end…

CH: Yes, a good point I will get back to discussing AD experiences of other directors. For still, I was not giving up on my original idea and started to look at different careers. First in Italian Cinema, since we took Monicelli as a starting point. It seems quite logical to me that there exist established entry points for working in cinema: There are directors coming from working as AD’s, others that come from writing, then there are those that started out in departments like cinematography or editing…And in terms of Italian directors who started out as AD’s I immediately thought of Lucio Fulci and Michele Soavi, both filmmakers best known for their horror movies. With Soavi, this genre was also crucial in his career as AD. He worked with Dario Argento and Lamberto Bava. So here we can clearly see an influence and straightforward development. Soavi really was a protégé of Argento. Whereas with Fulci it is a completely different case, for we have to consider that Fulci was not a man of horror from the outset. Rather, as a director he comes from comedy—and the same goes for his time as a AD before that: He almost exclusively worked on films starring Totò including Roberto Rossellini’s Where is Freedom? (Dov’è la libertà…?, 1954) and many films by Steno. But this is not how Fulci is remembered at all. We can find a rather strange discontinuity here.

PH: As a counter-example I want to talk a bit about Jean Renoir. Many people who worked with him as AD went on making their own films and cited Renoir as an influence, almost like a father figure: Luchino Visconti, Jacques Becker, Robert Aldrich or Paulo Rocha, to name just a few. More or less explicitly, they all referenced Renoir later on. I sometimes wonder what they learned from watching his films and what they learned from being with him, working with him.

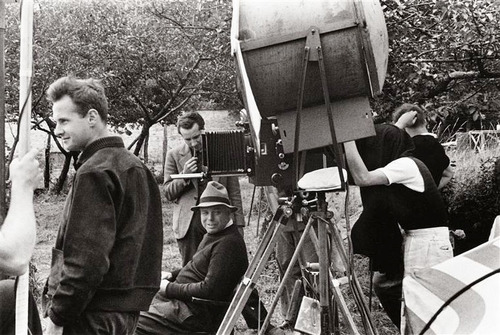

CH: In fact, I reread a lot about Aldrich because he had quite a spectacular career as AD. He not only worked for Renoir, but also for William A. Wellman or Charlie Chaplin, for example. There is a very useful book, “Robert Aldrich: Interviews” (edited by Eugene L. Miller, Jr. and Edwin T. Arnold, for the University Press of Mississippi) which contains a lot of god material pertinent to our subject. First of all, Aldrich states that his goal during his times as a AD was already to become a director. Of course there are people who are content to remain AD’s for life, but per Aldrich: “If you have any ambition and you don’t want to become a producer or writer, then you want to become a director.” And tying in with what you said earlier, he states quite explicitly about his AD experiences: “I think what you probably learn is what not to do as well as what to do.” And he goes into great detail about what he learned from the various directors he worked with, because each of them had his strengths and weaknesses. As for Renoir, he called him a “truly great filmmaker, not so much for what he did with the camera, but for what he did with the actors. He sincerely liked them and he had confidence in them. It was fantastic to watch him spend so much time explaining exactly what he was looking for. I don’t think he really cared where he put the camera, but still he knew exactly what he wanted.” Talking about others, Aldrich said that Lewis Milestone’s special talent was to pre-edit the films in his mind and shoot accordingly, or that Joseph Losey had an “absolutely extraordinary rapport with actors. I don’t think any other director I worked with ever had that kind of personal communication”, though he is quick to add: “Now, he has other limitations.” Yet Aldrich recalls strongly how Losey had the gift to create the best possible atmosphere on the set—and elsewhere mentions Leslie Fenton, a rather wavering craftsman, as counter-example, explaining that as soon as Fenton arrived on the set he would produce a foul mood, putting pressure on all crew members. Aldrich files that one as a prime example of having learned of what you do not want to do: He immediately decided to never work like that. But back to Renoir. Aldrich was his AD on The Southener (1945), a film shot on location, and vividly recalled the influence of the experience on his own methods of preparation before starting to shoot: “Renoir truly believed that a transfusion takes place from the physical surroundings to the performances and the picture itself. We would go on location, and he would walk up and down a riverside, for example, where we were to build the set, for two or three days. He would bring the actors there a week early, get them into costumes, and have them walk around barefoot. I found, as I grew older and directed pictures, that I didn’t really have to walk barefoot on the land to appreciate how to shoot or not to shoot. But getting the actors there, on location or on the set—or on the stage, for that matter—and having them in costume, in their parts, seemed to me to make great sense. I go on location as an assistant director, to see how the logistics are going to be. Is there a piece of rock outcropping, or a place where I can put the house, the barn, the corral, or the chase, so that it will work photographically? Could a guy come around the corner? Could he fall of the rock? I look for the practical things on location first, the artistic things second.”

PH: I think this describes in a great fashion what you can learn as AD. The few times I worked as a AD myself I always experienced it as something that is very far from being a director. Yet the job functions like an entry ticket, considered as something very close to the actual work of a director. You sit right between direction and production—or, we can say: the art and the money, even if there is little money. Maybe also between risk and reason. So you can learn a lot about communication, about how to assert certain things. You can learn about what is important to certain directors and what is not. I also think that you learn more in pre-production than while shooting the film. While shooting you just run for your life, trying to keep the show going. Maybe there are films where it works differently, but that was how I experienced it. Being a AD on set is a profession closely related to screaming. Actually, it is mostly screaming. It really inverts Serge Daney’s statement about cinema being the art of whispering, whereas theatre could be considered the art of screaming. On the screen: yes. But on set? No! We also have to consider that being a AD can mean a lot of different things depending on the time and especially the mode of production we are talking about. Being a AD in Hollywood is completely different from being a AD for a low-budget production from Austria. The division of work I got to know is one in which the 1st AD makes the on-set announcement, organizes procedures both on the set and beyond, and communicates between director and production. The 2nd AD was responsible for the extras. So to me being a 2nd DA felt much closer to being a director, as one is involved in casting, costume and mise-en-scène decisions from start to finish. In Hollywood and elsewhere it can be completely different, though. There the 2nd DA might prepare the call sheets and work as a sort of backstage manager. You can really see that responsibilities increase the lower number in front of AD. While researching, I felt that the past as a AD is very important to directors who stress their craftsmanship. Monicelli is such a case. These former AD’s draw a parallel to apprentices becoming masters in their profession. There is an interview with Monicelli published as a book by Cinecittà Luce. In it one can see how important this profession has been for Monicelli. He starts by saying that he was the lowest kind of assistant, the one who was lighting the cigarette of the director. So, for him, there exist different levels of being a AD. To me this sounds more like what we would call an internship nowadays. He also talks a lot about organizing—but then, to contradict what I just claimed about apprentices, he also says how being a AD for him was “the exact opposite of what every apprentice would like to happen. To learn as much as possible.“

CH: This reminds me of Aldrich’s description about working his way up at RKO, starting out as a production clerk—“the lowest form of human life”, the guy who gets the coffee etc.—then working his way up to 3rd AD, 2nd AD, and so on…

PH: To throw another name into our conversation. There was also Sergio Leone who worked with a lot of directors and continued his career as a AD while he was already a successful director.

CH: Oh yeah, I think he claimed more than 30 AD credits.

PH: Yes, from De Sica over Camerini to William Wyler’s Ben-Hur (1959).

CH: And including Aldrich’s Sodom and Gomorrha (1962)! Though we must be a bit careful with those Italian credits. Sometimes they just had to give credits like these to Italian crew members for co-production reasons, even if they did not raise a finger. Still, at least we can believe Leone was working on films like Ben-Hur in some way or another.

PH: Another example that could help us to understand the whole affair a bit better is Claire Denis…

CH: Indeed, although as a AD she mostly worked for Robert Enrico, a director that seems to have very little relation to Denis’ own work. Yet, while getting her bearings in the film world, she started to work for people like Wim Wenders and Jim Jarmusch…elective affinities, so to speak. There is also something about the issue with 1st AD and 2nd AD that now came back to me: I recalled Jacques Becker, who was Renoir’s DA for a very long time. But they were also very close personally, really good friends going way back. So it was a bit more than just being your regular AD. Anyway, it is interesting that Becker liked to recount rather proudly how Renoir promoted him from 2nd AD to 1st AD, in ways which totally contradict your experience of this jobs.

PH: It must be or have been different in France.

CH: And one can also find statements by Becker about how he was allowed to direct certain scenes as Renoir 1st AD. In general, I have the feeling that Becker’s reputation suffered –and still suffers—a bit from having been Renoir’s assistant for so long. Even as Renoir himself was always full of praise for Becker, he would mostly refer to him as his assistant: the best man who had worked for him… Nevertheless, Becker regularly stated how Renoir influenced his own work tremendously. For example, if you compare their films, both strongly prefer to focus on more characters rather than just one protagonist. For me, Becker transformed the approach of Renoir into something his own. The same is true for Aldrich by the way: He claimed that the most important influence on him was Abraham Polonsky, especially the period at the short-lived leftist production company Enterprise in the late 40’s. What Aldrich had learned there from Polonsky, whom he assisted on Force of Evil (1948)—and also from Robert Rossen, who directed Body and Soul (1947) from Polonsky’s screenplay—was to focus on the integrity of character: He kept going back to stories of men who battle the status quo and stay true to themselves at all costs. It’s about self-respect and following through on your beliefs, even if it means total loss, possibly even death: “I probably will lose, but if winning means going along with that kind of system I’m not going to go along. And I think I have an outside chance of winning doing it my way.” Aldrich gives numerous examples of how he would deal with scripts he didn’t like so much by reworking them according to this Polonsky strategy.

PH: Here we can also think about the idea of a AD being a very good spectator, almost an admirer of a work he wants to see being made…

CH: Yes, there is the story of Becker seeing La Chienne (1931) by Renoir and approaching him saying: “I want to work for you”. The same goes for Clarence Brown, who was an engineer working in the automobile industry, when he was so impressed by the early silent work of Maurice Tourneur that he travelled far to meet him, announcing he wanted to work for Tourneur. After being accepted, Brown—who in interviews would refer to his French-born mentor “my god” —worked as a AD for Tourneur, even co-directing one of Tourneur’s best films The Last of the Mohicans (1920), taking over the production when Tourneur fell ill. Around that time, Tourneur helped to launch Brown’s own directing career, and if one looks at his films, one can see a close relation to Tourneur. It is in the way he frames landscapes or applies lyrical ideas, the way he uses lighting, there’s a direct lineage. So maybe there are cases where we can find a direct influence when the work of a DA is really closely tied to a director?

PH: I think that’s true. Especially when there is an initial enthusiasm…it is obvious since there are myriads of examples of influences without the work of AD’s involved. It is about the difference of what you see when you see a film and what you see when you work on a film. There are some interesting statements about the disappointment involved in bridging this gap, like learning about magic tricks, the disillusionment in What Now? Remind Me (E Agora? Lembra-me, 2013) by Joaquim Pinto, who worked as a sound person for Raúl Ruiz. He describes this disillusionment a bit. It is also a disillusionment that sometimes gets ignored by film criticism, just as you said in the beginning. How do the people who made the film look at it? How do you see a film without critical distance? How is it for the worker to walk into the building he built? I think truths can be found there as well as mistakes. It might be about the things that one cannot see in the finished film. But one sees them if one knows more about how it was made. Suddenly, meeting the worker can be a shock. Many can tell stories about meeting their big idol who ended up being a jerk.

CH: Which leads me to the case of Maurice Tourneur, chapter 2. His son Jacques also worked as an assistant for his father, a bit later than Clarence Brown. Jacques Tourneur started out with being responsible for very small tasks on set, then climbed the ladder, working as editor and/or 1st AD for his father after Maurice quit Hollywood and returned to France near the end of the silent era. It must have been a problematic father-son-relationship. There are quite a few accounts of Jacques and others how his father was a very difficult human being. Maurice seemed always more interested in images than in people, he was notorious for devoting more time to composition and light than to the actors, whom he almost considered a nuisance. I think one can notice that when one looks at his films, especially the silent ones. While Jacques stated that he learned everything from his father and he would never be as great, he became very invested in working with the actors and was known for being very good to the people he worked with. So while Jacques picked up on a lot of visual stuff form his dad and applied it in more subtle ways, he also corrected Maurice’s attitude towards humans. That’s maybe part of what makes Jacques an even greater director in the end, even as his father was indisputably one of the greats. So here we have a different kind of lineage and again a case, where a former AD arguably transforms—or even transcends—what he leaned from his mentor.

PH: Talking about close relationships, I also found two examples of AD’s who remained in that job for all their life. One day somebody should dedicate retrospectives to those cinema workers. The first one I want to mention is Wingate Smith, who was the brother-in-law of John Ford and worked on more than thirty Ford films from 1929 up to 7 Women (1966). This also adds an interesting perspective on Ford’s work being a family business. Yet, mainly I think ADs are employed in a very different manner…it is not such a close relationship, not a question of admiration but rather one of simple ties to production companies. So, I found another case which I call the Jack Causey Case. He is British and he worked on many different films from The Third Man (1949) to A Countess from Hong Kong (1967), all of which were produced or co-produced in Great Britain. He worked on a lot of co-productions with Hollywood. In the middle of his career he also had a phase working with Hammer Films. It seems to have been a tremendously rich career and I wonder about all the stories he could have told, all the knowledge about filmmaking this man must have had. Yet, the only thing I could find researching him is some one-liner about this or that actor. Well, I think the Jack Causey Case is a typical example of a AD being closer to production managers than to certain directors. You have to love organizing, I think, you have to love the moment something works out on set more than the finished film.

CH: Naturally I also searched for such a case and found it in Claude Binyon, Jr., a name I had never encountered before. He has over 100 credits working as a AD, working on many films one hasn’t heard about. Then suddenly famous films pop up in between, like Westworld (1973) or That’s Entertainment (1974), also outstanding TV work like The Outer Limits in the 1960’s. So there is this strange meeting of film history and forgotten works.

PH: If I’m not mistaken, there are not nearly as many examples of AD’s becoming directors in Austria. One could think about the close relation of Michael Glawogger and Ulrich Seidl…

CH: We also shouldn’t forget that Austria is not one of the big industrialized cinemas. I think in many cases following this career path demands an industry. France is a good example. There, people like Costas-Gavras or Schlöndorff worked as AD’s for the same directors around the same time. Yet Costa-Gavras gave an interview in which he stated that being a AD in France means something completely different than in the USA, saying: “In France one used to be the right-hand man of the director.” We also shouldn’t forget Japanese Cinema, though I know too little about the process in detail. But they had strict regulations in their studio system. You had to work for a certain amount of time as AD in order to climb up the ladder, but the climb would be guaranteed. We can find many examples of directors whose career is a continuation of what they did as AD, but on the other hand someone like Akira Kurosawa also started off with comedies, almost like Fulci: He assisted on many films with the popular comedian Enoken, yet for a long time it was considered astonishing that he had cast Enoken in his film They Who Step on the Tiger’s Tail (Tora no O o fumu otokotachi, 1945). In any case, in Japan there was a system that asked basically asked its hopefuls to learn something from being a AD before they could become directors.

PH: Often we can learn more about the film industry or culture of a certain place or time than about auteurs by looking at AD’s. Additionally, it is also a strange question of hierarchies and power. You are asked to bend down a lot, to light cigarettes, as Monicelli describes, in order to learn something.

CH: Aldrich talks about it, too. He also mentions the cigarette but he says that it was an important task since it influenced the mood of the director.

PH: Well, to come to a finish: I have found one of those ridiculous lists on the internet where you can learn about what kind of character traits you must have as a AD…it talks about a positive approach, being flexible, being able to work long and unusual hours, multitasking abilities, being good in dealing with problems or crisis situations, having tact and diplomacy skills, paying close attention to detail, communication skills, planning ahead, having exceptional organization and time management skills, being a team player, being authoritative. To me it seems like a crash course in the reality of film-making. I imagine someone with, let’s use an out-of-fashion term, a vision of life and cinema. He or she comes to the world of film and then has to be a team player, has to communicate and so on. Nobody cares about this vision, about ideas, everyone cares about the payment and when to get home. I think to learn about that is very, very important. I also think that many fall through that test. Of course, there exist many directors that have a different path and that’s also okay. Yet, I think for Monicelli it was a logical path.

CH: Yes, he blossomed within a team, as a worker of comedy. I think this whole discussion leads back to an idea that doesn’t look at film history from an auteurist point-of-view. That is not how film productions work. It is mostly communal work.