Nicolai Gütermann

Like a jinn from a bottle, the mandarin rises from a palm-sized figurine to a fully grown human projection – the statue that came to life: the magic of cinema. The antagonist whose name and function give the film its title can, in a play on words, very literally be considered a Geist – a ghost. On the opposite end of the central narrative conflict, we find a young baron whose rather ridiculous problems of unrequited love lead to his madness and downfall. The frame of this story is an insane asylum where our fallen baron is condemned to spend the remainder of his days. How could he truly hope to ever be healed from the mandarin’s spell?

Framed within this subplot, the main story – the one of the baron’s demise – is told to an inquisitive journalist by the director of the mental institution. The baron’s case is presented as “Il caso più interessante”. In his retelling of the story, the doctor distinguishes neither between fact and fiction nor between objective events and the delusions or phantasms of the protagonist. The story is told through the baron’s eyes and therefore his ghosts become our ghosts. It is up to the viewers to decide whether they believe in the conspiracy of the mandarin’s spell or are witnessing the delirium of a mad man. Therefore I propose to do something similar in thinking about the film Der Mandarin. I suggest to regard (this) film neither as a pure work of fiction nor as a document of its time, but to let these two tropes exist simultaneously and equivalently: seeing Der Mandarin (or the cinema of those times) as a balancing act between an escape from morbid reality and everyday struggle in concrete images and narrative and at same time serving as a record capturing and processing those traumas in the subtext.

On November 22, 1918, nearly a 100 years ago, Der Mandarin was first publicly screened in Vienna. Only 11 days earlier, on November 11, the Habsburg dynasty, which had lasted for more than 600 years, ceased to exist. With the Austro-Hungarian Empire’s unconditional surrender, the “Great War” had come to an end and with it the Habsburg Empire had collapsed. The turbulence and precariousness of these times cannot be overstated. After the harsh winter of 1917, accompanied by more and more protests for peace, the people became aware of the inevitable defeat. No war is great. Yet, this one was particularly “ungreat” for the population. Not only did millions of soldiers died on various front lines, the war took its toll on large parts of the civilian population as well. Especially in densely populated areas, like the city of Vienna, heating fuel like coal was in short supply and, most importantly, the food shortage led to a rise in civilian deaths, thus coining the term “Heimatfront,” the home front. Additionally, the influenza pandemic, commonly referred to as the “Spanish Flu,” cost tens of millions of lives in Europe alone. Everybody’s life was in danger – everybody was suffering the consequences of war. So there might have been many a good reason to spend one of these days in a cinema – not least of all to escape the cold of home and distract oneself from famine. And cinemas, more than 150 of them in Vienna at the time, were relatively easy to maintain when it came to personnel and logistics. Furthermore, they presented a low-threshold pastime: they were cheap, open to everybody and even women could attend screenings unaccompanied, which would have been deemed unseemly in the case of theaters or even a Kaffeehaus, the Viennese coffee houses.

Der Mandarin was released in at least six of Vienna’s inner city cinemas simultaneously, with multiple screenings a day, adding up to approximately 2600 seats. Most advertisements focused on the film’s cast. They depicted the silver-screen debuts of two beloved theater actors as an antagonistic duo: Karl Götz (Volkstheater) as the mandarin and Harry Walden (Burgtheater), considered a star of his time, as the baron. The film was directed by Fritz Freisler and produced by Sascha-Film. The production company had been founded in 1910 by one illustrious Baron Alexander Joseph Kolowrat-Krakowsky whose nickname Sascha gave the company its name. Baron Kolowrat had successfully used his prewar status and connections to get a profitable contract for making war propaganda films and, more importantly, saved many great film talents from front duty by requesting them for his film division. Along with the baron, the Empire’s entire film production scene had profited from the war, not least because of the embargo on foreign (enemy) films which had been imposed shortly after its outbreak. Fritz Freisler had been working on the films of the “Isonzofront” and the propaganda film Wien im Krieg (1916), produced for a large war exhibition, before he made this film. Der Mandarin is the adaptation of the stage play of the same name written by Paul Frank, an author associated with the loose literary circle around Arthur Schnitzler and Hugo von Hoffmannsthal.

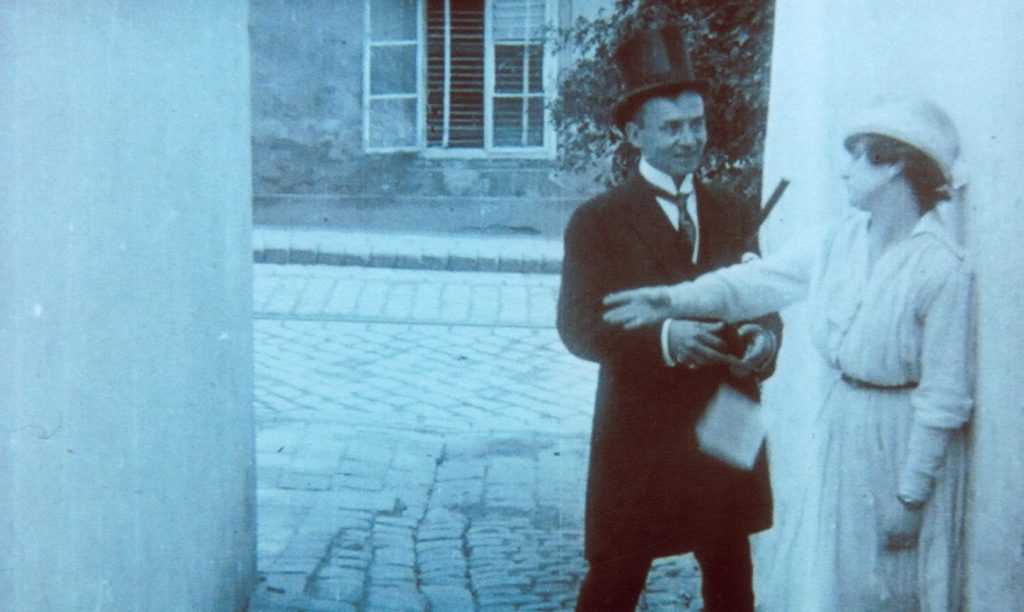

In this narrative, the young baron, a dandy and bon viveur, is consumed by his unrequited love for a famous opera singer. In a moment of despair after yet another rejection, he is approached by a street peddler who offers him a mandarin figurine with the promise to put an end to his pain and woe. To the wary baron’s surprise, the statuette comes to life and fulfills its end of the bargain, delivering the desired woman straight into the baron’s arms. After that, the effortless conquest of women without a trace of resistance leads to a vicious cycle of ever more outrageous requests: a married woman, a young girl carried away under the watchful eye of her chaperone and a lady stepping out of a painting directly into the baron’s embrace. However, the baron grows weary of these easy conquests and yearns for the amorous play with an uncertain outcome. That’s when he learns of the drawback of the pact: from now on, he will never again be able to attract women without the mandarin’s influence. The baron, driven by his successes and blinded by illusions of grandeur, laughs in the mandarin’s face and decides to fend for himself. The inevitable happens and the baron is rejected time and again: first by a lady of his social class, then by a gypsy dancer in a cabaret, and finally by a harlot of the streets who refuses his money. In all these rejections the mandarin appears as obstacle – a saboteur actively averting romantic prospects whilst taunting and ridiculing the baron in his defeats. The prostitute’s rejection is the final straw. Once the baron realizes that not even his money can save him from this curse, his downfall is sealed. After falling into a state of delirium, he is interned as a patient of a mental institution, where he is doomed to see the mandarin’s likeness in his doctor’s face.

The incentive for cinema and its impetus in these precarious times is distinctly escapist and the war is foremost manifested in its omission. The same holds true for Der Mandarin, a fantastic film on the joys and sorrows of love, without any figurative representation of the traumas of war. And yet, at the same time, many of these traumatic experiences are negotiated underneath the surface in the film’s subtext rather than in its concrete imagery. A young baron develops an omnipotence complex and falls victim to his fantasies of swift and effortless victories, which leads to a collapse followed by castration. In the very same moment, the same is happening to aristocracy as such and, furthermore, the whole empire. The very same delusions of grandeur that the Viennese aristocracy nurtured before the war ultimately led to the downfall of this societal and political system. Embedded in a tale of phantasms and illusion, Der Mandarin tells a tale of very real specters haunting these times. And audiences of yore and today are left with the same question: On which side of the institution’s walls is the saner of the worlds to be found?