Christoph Huber

A belated note on our recent retrospective devoted to a special strand of Weimar Cinema, which gave me the opportunity to (re-)watch two early films by Robert Siodmak on the big screen, always a pleasure–after all, among the many important exile filmmakers which ended up in Hollywood after the Nazis usurped Germany, Siodmak may be the most intriguing. That does not necessarily mean he was the best of the lot, but he had really remarkable careers in three countries: First, at home in Germany up to 1932, and then in France from 1933 to 1939, before he made it to the US. Many emigrants worked elsewhere in Europe on projects before they came to Hollywood, with these crucial moments in their filmographies often neglected, but few managed the constant output Siodmak sustained not only through these critical times, but almost up to the very end of his career in 1968.

Siodmak established himself as one of Hollywood’s major noir directors during the 40’s–which retroactively sounds great and stylish, although it is worth pointing out that during the heyday of film noir the designation did not really exist, as the term noir was hardly acknowledged outside of France, and thus the major cachet assigned to it is somewhat deceptive–, with occasional detours, e.g. into colorful adventure, as in that epitome of camp, Cobra Woman (1944), or the magisterial, athletic swashbuckling of The Crimson Pirate (1952). As with most exiled filmmakers, Sidomak’s work back in Europe upon his return in the mid-1950’s, is mostly considered disappointing, although the handful of examples from his “fourth career” I’ve seen, especially Nachts, wenn der Teufel kam (The Devil Strikes at Night, 1957) and L’affaire Nina B. (The Nina B. Affair, 1961), seem to prove the opposite.

With my cursory knowledge in both fields, the image conjured by Siodmak’s late period is not so different from the one I have of the early German and French films–given the usual adjustments for historical changes in style, acting, craftsmanship etc., they bracket his better-known Hollywood work quite satisfyingly, even logically. But of these two phases, only Siodmak’s early work is usually treated with a certain regard, even as it remains overshadowed by the opening stunner of his semidocumentary (co-)directing debut Menschen am Sonntag (People on Sunday, 1929), prefiguring the Nouvelle Vague approach with brother Curt and other future exile notables (including Billy Wilder, Edgar G. Ulmer, and Fred Zinnemann.) Finally reencountered on a big screen, Siodmak’s second feature, Abschied (Farewell, 1930), never quite achieved the same reputation, but feels no less of an achievement, using the cross-section approach to society so popular in Weimar cinema for a lyrical tragicomedy set in a Berlin guesthouse, populated by life’s disappointed. It is one of those films that in hindsight seems to exemplify all the qualities and ambiguities soon to be mostly purged from German film by the fascist regime.

Otherwise filled with delicate nuances (one remembers it as a quietly devastating film), Abschied is both upfront and remarkable in its use of sound–in fact it was the first sound production for Germany’s big studio UFA, entrusted to the newcomer Siodmak on the basis of his breakout success with Menschen am Sonntag. A good choice, as Siodmak shows a cinematic sensibility energized by enthusiastically exploring new opportunities and ideas–the sometimes daring stylizations of Siodmak’s Hollywood shadowplays seem within reach: Like Fritz Lang in M (1931), Siodmak shows an intrinsic understanding of the possibilities of sound, but gravitates towards entirely different tones and effects–again, one can intuit how both would fill the Hollywood noir vessel with their quite different, but equally doom-attracted Germanic predilections. Thus, in Abschied we get not only shots devoted solely to such new cinematic events as clocks ticking in close-up or the detailed study of a vacuum cleaner in use, but also moving, transient images like the long-held sight of an ashtray on a bedside table, in which cigarettes slowly burn up, while we hear a nearby couple’s off-screen dialogue, conjuring a startling intimacy and tenderness–a powerful juxtaposition similar in essence to the grand gesture at the end of Sidomak’s noir Christmas Holiday (1944) with its Wagner sweep on the firmament, but still resolutely small-scale.

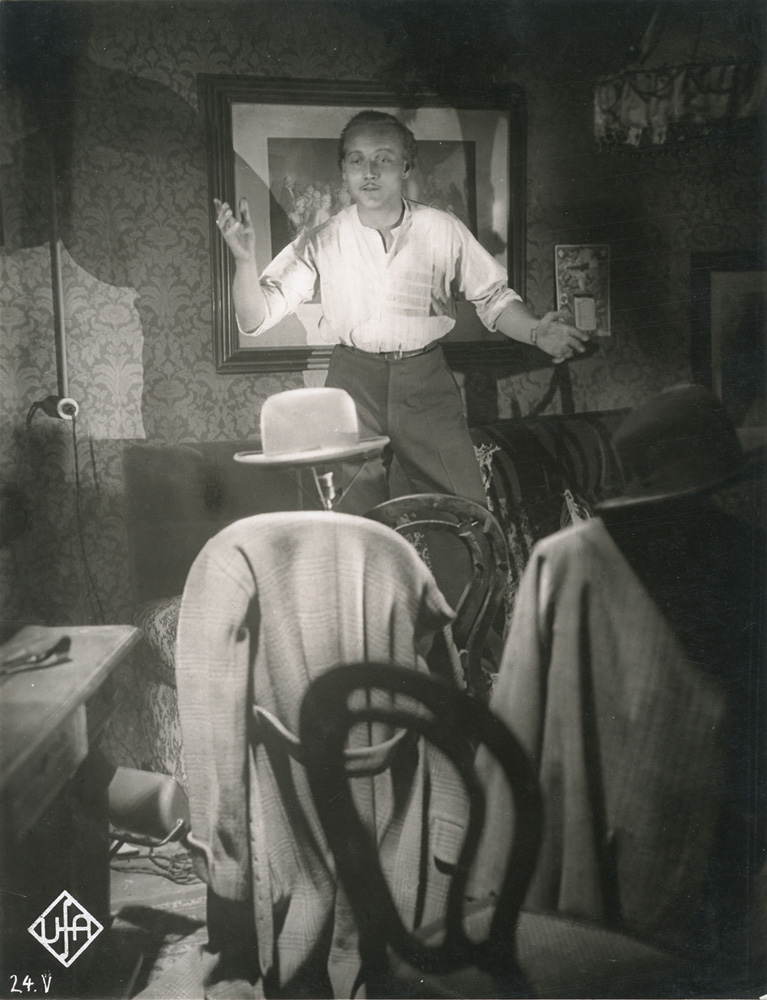

Curiously, the beautiful print we got, contained a second ending, not unlike the case I reported recently–though this time the alternate finale is identified as such, with intertitles announcing that the studio mandated a happy ending against Siodmak’s wishes (he did not shoot it). No Spoiler Fear, here: The curious thing is that nobody in his right mind would call that tacked-on, but laid-back additional scene a happy ending in the common sense, or even consider it conclusive. And yet, even more curious is the case of the second Siodmak film in our series, a veritable discovery, with the director starting to move from the realistically rooted, semi-plotless style of his earlier films towards the rhythmic elegance of the more stylized genre work he is best known for: Stürme der Leidenschaft (Storms of Passion, 1932) was long considered lost–when actually a Japanese German-language release print replete with kanji side-titles had survived in Tokyo’s National Film Center and had its belated European comeback only a year earlier according to my information. To make this whole story even more complicated, another version has survived, and surely qualifies as the biggest curiosity in this whole paragraph: The bizarro Italian item Tempeste di passione, which is essentially a silent–the original soundtrack had been replaced with a new musical score (keeping only a Friedrich Hollaender song), and Italian intertitles fill in for the dialogue.

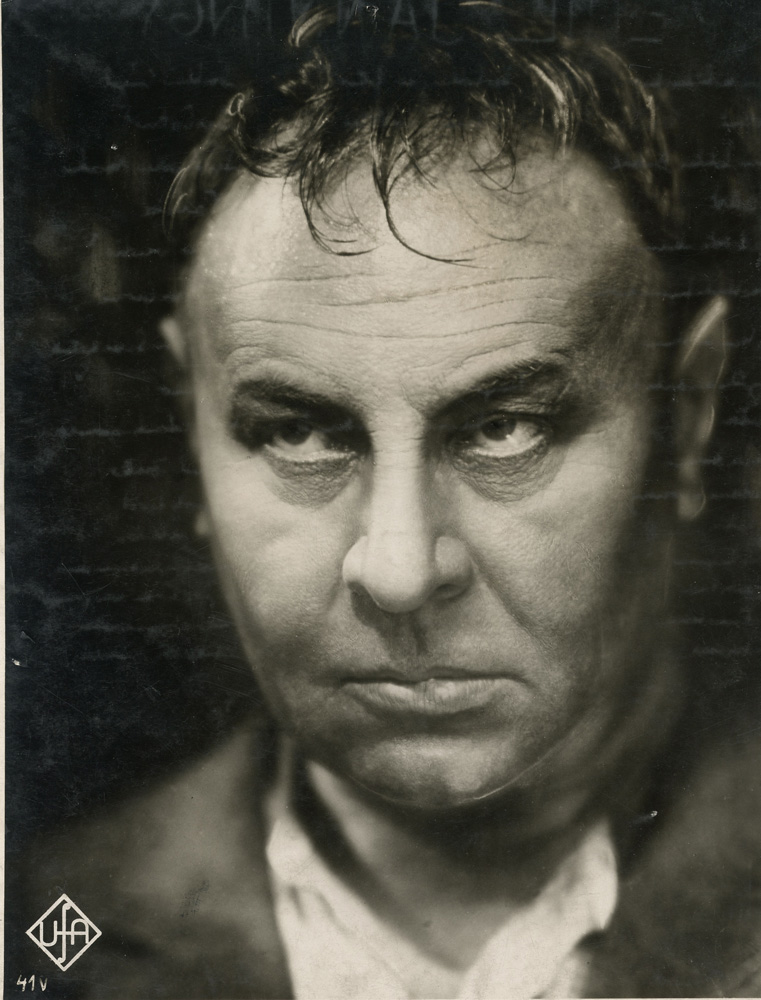

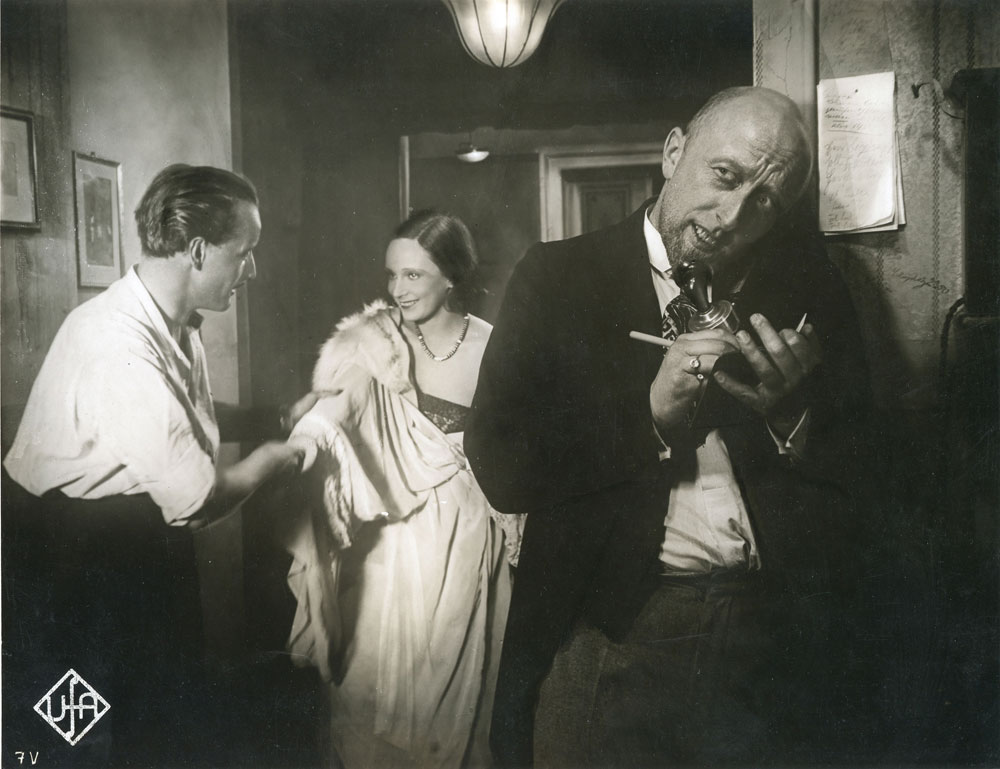

And then there’s Tumultes (Tempest, 1932), the French-language version shot by Siodmak with an entirely different cast, in which Charles Boyer is merrily heading an ensemble of Frenchmen that feels oddly misplaced in Late Weimar Berlin. In the German version, the lead character–who upon release from prison returns to his cheating girlfriend (Anna Sten in the best part of her German career) and criminal pals, with somewhat foreseeable consequences–is played by Emil Jannings, who is the greatest revelation of Stürme der Leidenschaft: His heaviness weighs down even some vaunted classics by Murnau and von Sternberg, but here he is a delight and, yes, often really funny, whether loosely exchanging patter or even pulling off a cheerful disguise-act to save his incompetent heist partners. (Despite the arc of a fatalistic gangster melodrama, there’s quite a bit of comedy, possibly presaging the mix of crime and musical romance in Siodmak’s Pièges [Personal Column, 1939].)

But imagine my surprise, when–enthused by the German film–I dug out a video copy of the French version only to discover that Tumultes contains no such disguising act. (Instead, Boyer helps the others digging downstairs.) Although generally following the same outline and using the same sets, the French version has a few such unexpected detours, most of them equally puzzling. (Surely, Boyer would have pulled of the disguise routine, so why the changes?) Overall, the French version comes across as a curiosity in comparison to the German one, though still a pretty impressive specimen. And, of course, the final and biggest puzzle remains equally intractable: Namely, what is missing in the surviving German version? As enjoyable as it is, that Japanese print of Stürme der Leidenschaft had been cut for its release, in a couple of instances quite notably. The remaining runtime is 82 minutes, when the film was originally submitted to the German censors at 104 minutes, with most sources claiming the original release length at 101 minutes. For one thing, the bizarre Italian version–which I have not seen–clocks in at 91 minutes when projected at sound speed (24 frames per second), but of course is “prolonged” by the added intertitles, whereas Tumultes is usually listed at 92 minutes (my VHS copy is three minutes shorter, which is fine, since it’s PAL, meaning a speedup to 25 frames per second).

I shall not cheat you, dear reader: I have no answer to that puzzle, I can only confirm that Stürme der Leidenschaft is a special treat even with cuts, and together with Abschied has reinvigorated my fascination for the lesser known areas of Siodmak’s work. And to be honest: At least this is a pretty clear-cut case, as far as the different versions and their stories are concerned–we know something is missing and can assign the lacking minutes to historical factors. Still, I know that with this post I’ve opened pandora’s box–because one of the things I’ve learned to mistrust in my new job at the Film Museum is the purported length of a film, even if there is offical agreement about its runtime. But I shall save some salient examples–I’ve encountered more than enough over the course of merely half a year–and a more detailed discussion of the dilemma for another post. For now, let’s stop here; with one more picture of Emil Jannings for your (re-)consideration.