Christoph Huber

Four years ago today, Jean Rollin died. He was the poète maudit among those obsessive filmmakers who straddled a thin line between porn, exploitation, and personal expression during the 70’s. This Frenchman occupies a special place in film history and in my heart.

Frenchman Jean Rollin occupies a special place in film history–and in my heart. He is the aesthete amongst a group of filmmakers I like to call the obsessives: Those directors who used the window of opportunity opening during more freewheeling genre times–roughly from the late 60’s to the early 80’s–to obstinately pursue personal paths, which often yielded remarkably uncommercial results despite the seemingly surefire ingredients of sex and violence.

Jess Franco may be the most legendary name among these (possibly unconscious) renegades in the bowels of exploitation filmmaking, which have long since become cult figures–just look at the amount of often deluxe DVD and Blu-ray editions for the fan circles, almost up there with those for the prestigious and popular pantheon members. Franco, sometimes called “the most dangerous filmmaker alive” thanks to a Vatican communique (maybe owing to the great tradition of the Spanish inquisition: the other main offender was Luis Buñuel), may have been the most prolific and most reckless purveyor of anything-goes in the wacky world of low-rent genre opportunities that exploded in the wave of 70’s Eurotrash–often serving sex and horror, but actually catering to many tastes, including that for hardcore porn.

Basically, at some point early in the decade, Franco decided to wallow in the lowest recesses of cheap and fast production in order to excessively indulge his personal preferences, even developing a private mythology with elaborate, though not necessarily coherent cross-references over the course of two-hundred-plus movies, mostly ignoring all tenets of conventional film, whether art-or commerce-driven–Franco’s notoriously pan-and-zoom-heavy, deliriously shoddy excesses may have been inspired by his love for free jazz improvisation, but they’re also an act of defiance: a large part of his œuvre seems to have been made strictly for his own pleasure and not that of any audience.

Similarly, in the US you have extreme demolition men like Andy Milligan, much-maligned for his lack of style–indeed it would seem impossible to defend him on formal grounds. But his lowest-budget-exercises have something else, and it is not pleasant: Here is somebody clearly wrestling with his own demons, resulting in films that are marked by a disturbing hate and terror, both sexual and emotional. And then there’s Jean Rollin, who is something of a poète maudit in the context of the obsessives, a lyrical soul blessed with an innate visual talent and an even more special sensibility, a fateful romanticism surprisingly tender for a filmmaker mostly associated with horror.

But Rollin’s inspiration was not exactly fueled by what is conventionally considered horror these days, certainly not its harder variants. He cherished an idea of the Fantastic as a dreamland. Indeed, most of Rollin’s movies play out as daydreams, their occasional bloody eruptions channeled in reveries full of mysterious and (softly) surreal elements. His somnambulant style is a perfect fit: fragile successions of quiet, at times aching, beautifully arranged tableaux alternating with declamatory dialogue passages of a more theatrical, sometimes almost Straubian nature. Rollin’s agenda was anti-materialist, however: His world is that of a dreamer. (He also was clearly less interested in acting per se than in the sheer presence of his actors.)

Born in 1938, Rollin fell in love with cinema early: Already as a teenager in the 50’s he devoured old serials (whose casually surreal bent may have left a mark). Later during that decade he served in the army, working as an editor in the film department, alongside future colleague Claude Lelouch, who would walk down more respected paths to chart l’amour et la mort. Soon, Rollin would make his first shorts, embarking on a career that seems inevitable in retrospect: Already these early works drew him to the Rollin place, a patch of beach which would become as dear to his fans as Monument Valley is to the admirers of John Ford.

Rollin’s first full-length work Le viol du vampire (The Rape of the Vampire, 1968) basically consisted of two shorts cobbled together to achieve feature-length: One of the few films to open in Parisian cinemas during that year’s tumultuous May protests, it drew enough attention–its characteristic mix of erotic and fantastic elements even cause a minor scandal–to launch Rollin’s first period, containing most of the films he is famous for: a series of haunted successions by sexy female vampires, mixing unfulfilled longings and uncanny apparitions in delicious and devastating ways. Rollin’s heroines (and the male folk as well) are lost ones, in the truest sense: In his hands, the supernatural elements transcend formulas and necessities of genre (just a peg on which to hang his state of consciousness, really), but rather feel like the natural extension of the filmmaker’s worldview, tinged by piercing melancholia and dark desires.

By the mid-70’s, Rollin’s difficulties in getting (t)his kind of personal work financed, led him to accept hardcore assignments, however begrudgingly. Usually working under a nom de plume–Michel Gentil and Robert Xavier were the preferred ones, if you can put it that way–, Rollin was not happy with doing porn. It shows in the films, although they are not without interest. Obviously, their maker was not particularly interested in the act (or its blunt depiction) per se, but in a more dreamy, engrossingly sensual idea of the erotic. A particularly instructive and curious case is Gentil’s parallel porn version of Rollin’s most celebrated female vampire hallucination Lèvres du sang (Bloody Lips, 1975), mercilessly cut down and spiced up for hardcore pleasure, resulting in the (at least) indelibly titled Suce moi vampire.

For a significant amount of time, Rollin occupied a genre crossing that is as intriguing as it is neglected: horror-porn-crossovers that surfaced, in the 70’s, as one of several short-lived afterthoughts to the era’s porn chic. One of the most fascinating examples of this peculiar breed is an unheralded gem from the US: Through the Looking Glass (1976) by Jonas Middleton, a serious, yet delirious phantasm (it more than justifies its titular Alice allusion) presenting a vision that is nightmarishly dark, even as supposedly pleasurable hardcore scenes are liberally sprinkled throughout–it even ends in a hellish wasteland halfway between Pier Paolo Pasolini and José Mojica Marins. The sadly short-lived career of its creator culminated after this, his third and last adult directorial assignment, with Just Before Dawn (1982), a solid backwoods slasher film of some repute: Middleton wrote the story and associate-produced for director Jeff Lieberman, fondly remembered for his LSD fallout horror Blue Sunshine (1978) and the electric-killer-earthworms romp Squirm (1976).

And Middleton is hardly the only notable example of fruitful horror-porn miscegenation: Danny Steinmann, destined for pulp pleasures like the glorious Savage Streets (1984) and the somewhat less stellar fifth part Friday the 13th: A New Beginning (1985), entered the field (under the pseudo-pseudonym Danny Stone) with a crazy kaleidoscope of slightly satirical porn called High Rise (1973: besting Ballard by two years). And Armand Weston established himself firmly in the adult field in the 70’s before failing to cross over into mainstream filmmaking, with his second project falling apart after he gave us The Nesting, a superb Southern Gothic ghost story that only hints at the directors previous work by being set in a brothel.

Both porn and horror can be made cheaply and thus potentially very profitably, which may explain one reason for their overlap–not to mention there’s the time-tested eros-thanatos connection… Still, it was probably the economic factor helping fresh talent to enter the business in the respective fields and adjacent exploitation territories–consider the concurrent careers of Abel Ferrara, Wes Craven, Sean S. Cunningham, William Lustig et. al. Meanwhile in France, even a mainstream veteran like Claude-Bernard Aubert–probably best remembered for L’affaire Dominici (The Dominici Affair, 1973), starring Jean Gabin and future Ferrara DSK Gérard Depardieu–could dabble without repercussions largely in hardcore delectation during the late 70’s and early 80’s, mostly using the moniker Burd Tranbaree.

In a roundabout way, this brings us back to Rollin, who embarked on a similar path, however reluctantly. Brigitte Lahaie, one of the great icons of French porn, became one of Rollin’s leading ladies at the time, trying a mainstream move and nabbing supporting parts e.g. in Henri Verneuil’s superb political thriller I… comme Icare (I as in Icarus, 1979), while doing double duty in sex and horror, her triumphs in the latter field including two of Rollin’s most extraordinary works, Fascination (1979) and La nuit des traquées (The Night of the Hunted, 1980), the latter crying out to be shown as a double feature with David Cronenbergs “official” debut Shivers (1975) as a memento to sterile high rise culture crumbling.

Although he’s automatically associated with vampire movies, there’s more variety to Rollin’s career, even as his occasional descents into hypnotic monotony suggest a singular drive, maintained erratically, but beautifully, still poised with heartbroken, heroic panache in the face of adversity: Ultimately, he emerges as the only great French director of the Fantastic during the era of modern horror, although recommended outliers exist–one of the most notable, reliably, coming from the nation’s eternal renegade Jean-Pierre Mocky with his comical parade of the dead, Litan (1982). Even more astonishing in the light of cinema’s frequent failure to adapt H.P. Lovecraft is Le démon dans l’île (Demon Is on the Island, 1983), a striking concoction that is more Lovecraftian than most official adaptations, not least because it isn’t obviously so.

Le démon dans l’île is one of the the rare mainstream efforts of porn specialist Francis Leroi, a Nouvelle Vague associate in his upstart days, advertised on the video cover of at least one of his hardcore exercises as “the former assistant director of Claude Chabrol”, though I can’t say if it was Couples voyeurs et fesseurs (aka Jeux de langues, Voyeur and Spanker Couples and Sex Maniacs 2, 1977), his sublime sado-porn variation on Rear Window (1954), or one of his efforts with Brigitte Lahaie, undertaken around the same time she bared herself for the cameras of Aubert–and Rollin. Thus, a circle closes, which for Rollin may have been a circle of hell. By then, he had also been forced to add more violence to his films. He was not too fond of gore, either, it seems, but once again yielded to the demands.

My favourite Rollin film La morte vivante (The Living Dead Girl, 1982), is a good case in point: It contains only a handful of blood and guts, but those moments are still pretty strong, even from today’s jaded perspective. One could argue that they mesh somewhat incongruously with Rollin’s more yearning–and, in this case, visibly more streamlined, but still lingering-dream-state–approach towards the inevitable. There is at least half a dozen other Rollin films I like almost as much, including Fascination (plugged by Steve Erickson in his great movie-novel Zeroville) and especially La rose de fer (The Iron Rose, 1973), which could be described as mournful nightly stroll through the graveyard towards tragedy, to give an idea of Rollin’s low-budget resources and resourcefulness.

But what distinguishes La morte vivante is that it comes at a point when Rollin’s ambitions–you could also say: pretensions, not only to achieve something personal, but something artistic, initially even arty, against all odds–have eroded under the pressure of all these years. Clearly, the necessities of business had hardened him by then, but the remnants of the tenderness and pain that distinguish his work radiate even more strongly, glistening with hard-won knowledge. Still, you couldn’t claim that disillusionment had turned Rollin into a realist: Just witness the inexplicable toxic spill opening of La morte vivante that sets the plot in motion–a good example for Rollin’s treatment of the surreal as self-evident.

La morte vivante is also something of an ultimate achievement. It is quite literally about the hurt in the process of valediction and a loss which cannot be compensated by even the most pronounced desire. Rollin’s own sufferings as an obsessive director forced to compromise his vision transformed into a plaintive cruel story of eternal love (and death)? He never could stop filming–he continued up to the end, often in ultra-cheap video productions that nevertheless bore his unmistakable stamp.

Rollin died on December 15th, 2010–the same day as Blake Edwards, whose incomparable slapstick comedy The Party (1968) creates an entirely different kind of depressive horror. Earlier that year, people proclaimed the end of a cinematic era when Ingmar Bergman and Michelangelo Antonioni died on the same day, but their art(ist)-film model lives on, admittedly in a different form, for different times. But the passing of Edwards and Rollin seems much more significant, representing the end of a certain way of making movies personal in a commercial context. Only their ghosts remain, to haunt us.

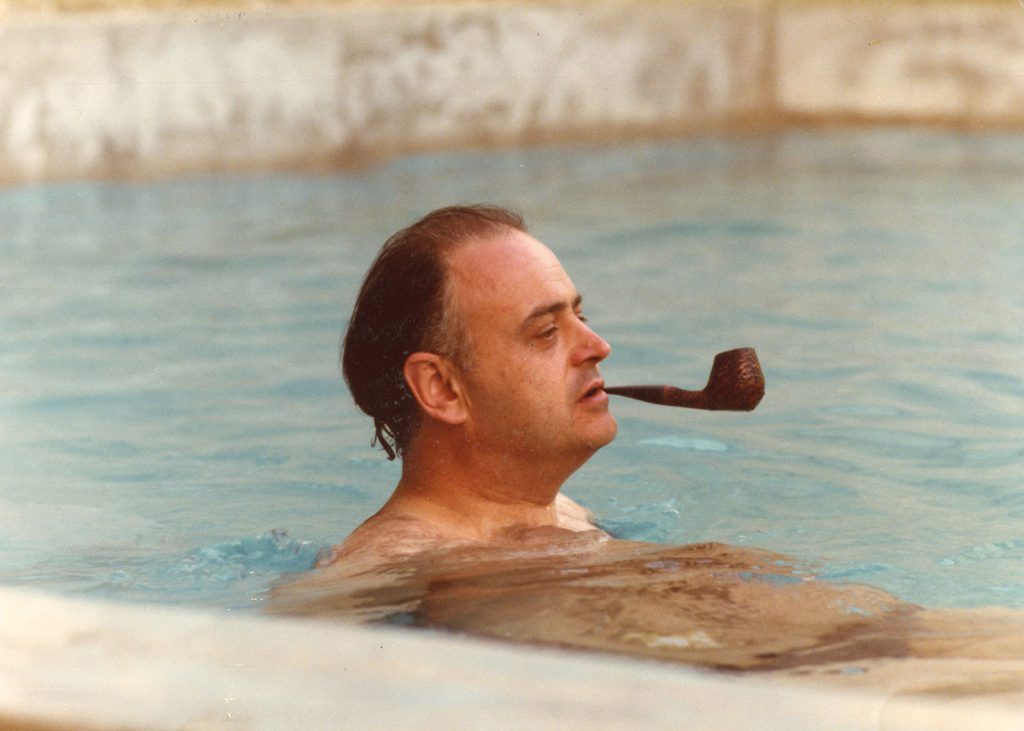

Photo: La Cinémathèque de Toulouse

Adapted from an introduction I gave to La morte vivante during the second part of horror series I curated for the Austrian Film Museum, Land of the Dead.