Christoph Huber

A popular and brilliant actor, Vittorio De Sica proved himself an outstanding director as well. Unfortunately, his reputation as a filmmaker is defined almost exclusively via his famous neorealist classics. Big mistake. A note on the dynamics on film history.

“Ze wrong man has escaped!”

These immortal last words–uttered by the titular trickster (played by Peter Sellers) in Vittorio De Sica’s Caccia alla volpe (After the Fox, 1967) as he realizes that his disguise is so cunning he has fooled himself (maybe you have to see it to fully appreciate the gag)–just seemed a great punchline to me when I saw the film several times as a kid. It was just one of those comedies they used to play every other year during the post-midnight marathon national television habitually programmed on New Year’s Eve. Only later, I kept flashing back to that moment whenever I thought about the conundrum of Vittorio De Sica, misunderstood director. I fell prey early to that misunderstanding myself: During my teenage years, when–a budding cinephile–I first delved into tomes about film history and belatedly grasped who the director of Caccia alla volpe was. Let’s just say, I found it hard to realign this colorful romp with the concept of “De Sica” I encountered in the history books–how come the acclaimed director of serious Italian neorealist classics presented this gift for this young Sellers fan, weaned on cherished reruns of Blake Edwards’ Pink Panther films?

Don’t get me wrong: I haven’t seen Caccia alla volpe for some 30 years, but back then I just found it (repeatedly) hilarious. The confusion started later, when I was confronted with Vittorio De Sica, key auteur of neorealism, and seemingly given to altogether loftier ambitions. In retrospect, that construct probably should have been filed under “De Sica”, one of those received-wisdom cement blocks that make up the mainstream of film history but don’t necessarily hold up once you consider history a dynamic process–the more we discover, the more alternate paths open up, rendering certain ideas obsolete (that does not mean they were useless in their time, just their unthinking prolongation is–after all, even films themselves can take on entirely different meanings over time). In fact, the “De Sica” construct didn’t even work for me back then, and not just because I saw myself as a card-carrying existentialist averse to emotional outpours: Encountering his alleged masterpieces, I felt sorely let down, especially when weighed against the contemporary achievements of Roberto Rossellini. De Sica’s Sciuscià (Shoeshine, 1946) and Ladri di biciclette (Bicycle Thieves, 1948) seemed outdated sentimental tracts in comparison to Rossellini’s modern filmmaking, and especially the earlier film did not even come across as very realistic, its supposedly revolutionary location shooting not the revelatory center of the proceedings, but more of a backdrop for the tightly developed and cleverly constructed, but ultimately theatrical dramatics. I found it easier to appreciate De Sica’s directorial skills as demonstrated by the nimble, stunningly successful dedramatization of Umberto D. (1951), probably the most fully achieved of his classics–but shortly thereafter, an unfortunate encounter with the surrealist proliferations of Miracolo a Milano (Miracle in Milan, 1951) led me to give up early on De Sica as a director, mostly underwhelmed by his canonized quartet.

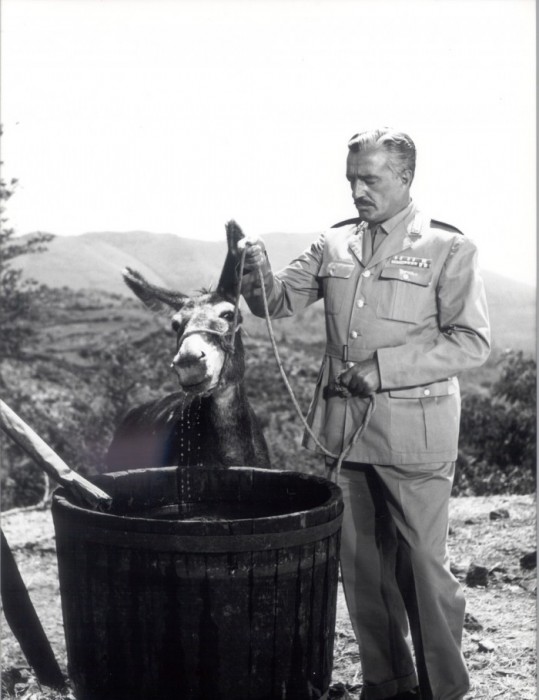

Still, something kept nagging inside me, and not only when I came across quite interesting De Sica contributions in a handful of episode movies. Even more fascinating was the allure of the brilliant actor De Sica, whom I encountered more frequently and who always left the impression he must know a thing or two about directing as well (actually, he repeatedly did direct parts of movies on which he only has an actor’s credit). De Sica’s spellbinding onscreen presence, second only to the donkey in Luigi Comencini’s Pane, amore e fantasia (Bread, Love and Dreams, 1953), suggested deeper layers in the way it consciously, affectionately and ironically played with his popular image, most famously his well-known gambling habit, parlayed into prize parts like the title hero of Mario Camerini’s Il signor Max (Mister Max, 1937), and spoofed most ingeniously in De Sica’s own superb anthology L’oro di Napoli (The Gold of Naples, 1954), casting himself in one episode as an aristocrat who has been put under tutelage because of his gambling addiction and is reduced to playing cards with the concierge’s little kid. (What’s worst, he keeps losing.) With the consummate professional’s ease, De Sica was also capable of effortless changes of register–from delicious ham to precise, subtle characterizations, depending on the part–, which further hinted at a range I had missed in his famous directorial work. After all, wasn’t his superb performance as an impostor for Rossellini in Il generale Della Rovere (General Della Rovere, 1959) some form of conscious atonement, adding to the complexity of a great film?

The eminently recognizable and seductive persona De Sica cultivated as an actor–usually a swindler of considerable charm, but with a disconcerting hint of sleaze–came across as yet another “De Sica” quite at odds with the one on file, who is usually considered an artist who peaked early in neorealism only to increasingly squander his talent on more commercial assignments during the subsequent decades. Maybe befitting his image as a trickster, he was automatically and almost exclusively associated with a momentous moment in (film) history that in hindsight can be recognized as a construct itself, albeit a necessary one: the birth of neorealism after the war, forcefully dedicated to humanist values and, most importantly, a materialist appreciation of the actual world in opposition to the artificial images of the “dream factory”, was perfectly in tune with the ideas of postwar reconstruction. And although this decisive, allegedly truth-searching turn towards reality captured the cinematic zeitgeist and exerted considerable practical and theoretical (cf. André Bazin) influence for the time to come, the sudden birth of Italian neorealism right after the war is a myth–like most claims about “revolutions” in cinema, usually simplifying complicated and messy developments out of need for compression or the sake of an argument. These neorealist tendencies had been around for quite a while, at least since the early 1930’s–even De Sica himself had basically been there before the end of WWII.

Additionally, De Sica’s neorealist classics started to fall out of fashion in a way, evidenced for instance by the downslide of Ladri di biciclette on the Sight & Sound Top Ten Lists over the decades. The historical importance of his four celebrated films remained mostly undisputed, but their sincere, if often overbearing feelings seemed increasingly out of step with more cynical times. De Sica remained a household name, not least thanks to his popularity as an actor, but his famous quartet’s reputation was the always-dubious one of a touchstone for previous generations, tragically underscored by its lionization in the work of Woody Allen, that paragon of middlebrow taste. Retroactively, De Sica’s neorealist classics came to be seen not as auteurist achievements, shaped solely (or at least: mostly and decisively) by the director, but as collective products, whose power clearly derived from several creative departments, starting with the input of writer Cesare Zavattini, key proponent and theorist of the movement.

And rightly so–although it should be noted in the same breath that many of De Sica’s key collaborators kept working for him, most notably Zavattani, his preferred writer, contributing on two thirds of De Sica’s official filmography up to his posthumously released Il viaggio (The Voyage, 1974)– actually, their professional relationship had begun prior to Sciuscià. Furthermore, there’s the formal question: While De Sica’s work is ripe with recurring themes and interests, he never subscribed to a signature style, floating with the times in every sense, even submitting his (kind of) “Nouvelle Vague” film with the Paris-set Un mondo nuovo (A Young World, 1966). Obviously, De Sica saw himself simply as a popular filmmaker, tailoring his mise-en-scène according to the job, no less dedicated to being a professional craftsman than in the acting department–he may not have succeeded as smashingly overall (who could?), but there are remarkable riches to be harvested throughout his career.

To attack the issue from behind, De Sica’s perceived directorial decline especially in the 1960’s can only seem ludicrous in the face of a key film like Il boom (1964), a conte-cruel/comedy in which Alberto Sordi suffers the consequences of the economic miracle–the nouveaux-riche interior design alone is the stuff of nightmares–in a brilliant succession of gags, barely concealing the dark currents seething beyond De Sica’s much-touted tender touch. (Still, especially Sordi’s child-like side is allowed to shine here, a favor repaid three years later, when Sordi–himself an actor-director by then–cast De Sica as his papa, naturally a ne’er-do-well prone to gambling and women, in his sweet-sour comedy Un italiano in America (An Italian in America).) The sarcasm of De Sica’s contributions to the grand, gnashing onslaught of Commedia all’italiana–Il giudizio universale (The Last Judgement, 1961) is a grim moral tale exploded into rambunctious episodic excess with an international star cast of dozens (spearheaded by a truly creepy Sordi, playing the “merchant of children”)–spills over into a surreally serious work like his underseen Sartre adaptation I sequestrati di Altona (The Condemned of Altona, 1962), which must have alienated many back in the days, but has improved with age, maybe because its weirdness by now registers as only appropriate: the boom this time around is the Wirtschaftswunder of West Germany, the nation in a state of hotly debated rearmament, its self-deception and still-festering guilt about the war mirrored in the fate of a wealthy clan (adamant patriarch: Frederic March). Quite literally: the son (Maximilian Schell) is a war criminal, who has remained hidden in the cellar since 1946, still parading his uniform. His belated trip to the outside does not turn out as expected, for him or the viewer: Finding the country not in ruins, but decadently celebrating the fat years, he climactically stumbles into a performance of Brecht’s The Resistable Rise of Arturo Ui, freaking out completely–when his chants of “Sieg Heil!” fill the auditorium, the alienation effect has been squared, if not cubed.

In several ways, these astonishing late-period works–De Sica, born into poverty in 1901, died in 1974, still pursuing various projects–hark back to the beginnings of De Sica’s directorial career. After starting in the theatre, he became one of the most acclaimed leading men of Italian cinema in the 1930’s and took up directing in 1940, at first contributing remarkably sophisticated comedies to the nation’s then-dominant, carefree and reality-averse wave of “white-telephone”-filmmaking–the highlight of this first phase probably being Teresa Venerdì (Doctor, Beware, 1941), which features some surreal touches that wouldn’t feel entirely out of place in one of those deceptively made-to-order Mexican movies of Luis Buñuel. The turning point came with a film shot in 1942, but only released in 1944: I bambini ci guardano (The Children Are Watching) was not only De Sica’s first foray into drama, but also the first time he did not act in one of his movies. More importantly, the crucial elements for his neorealist classics fell into place right there–down to the child’s perspective, relating the story of a crumbling marriage from the vantage point of the little son. Even Zavattini got his first scriptwriting credit on a De Sica film, after previously contributing unacknowledged to Teresa Venerdì. However, I bambini ci guardano differs considerably in tone from the famous films to follow: With wild mood swings and a palpable rawness, it works almost antithetical to De Sica’s smooth, dynamic classics–an all-enveloping feeling of enclosure and stark pessimism tells its own story about life under fascism. (Little wonder its release got held up: a truly unhappy childhood and adulterous mothers were not exactly subjects endorsed by the Fascist regime.)

No less striking is the long-overlooked La porta del cielo (The Gate of Heaven, 1945), shot during the final period of WWII–begun after Italy’s total capitulation in September 1943, and still underway when the Allied forces liberated Rome on June, 5th 1944, its production has attained legendary status, though much of that is, alas, really just legend. Made in close collaboration with the Vatican, this Very Catholic Pilgrimage culminates in a miraculous and increasingly delirious, even exhausting church scene (shot in the basilica of St. Paul), making the nation’s notion that it needs to be healed seem less like a hopeful promise than a crazy collective fever dream. De Sica considered La porta del cielo one of his best films, and his pronouncedly Christian approach can be traced further in Sciuscià and Ladri di biciclette, which present their own peculiar blend of that quintessentially Italian mix of Communism and Catholicism. Although struck by many such unexpected connections when I re-watched these two films, my main problem remains (and to drop a contemporary non-sequitur, I am strongly reminded of my problems with the most recent work of today’s realism-role models Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne): Their (admittedly cunning) construction is so airtight that any idea of realism goes intermittently out of the window, even as Ladri di biciclette actually does some amazing things out in the streets, which come to feel like a labyrinth for its increasingly desperate protagonist. Less so Sciuscià, which plays for its biggest stretch like a Warner Brothers prison movie with a kid cast–no mean feat in itself (even the lapses into sentimentality might befit, say, one those vehicles with Bogart and a tyke, despite their roots in actuality), proving De Sica’s impressive directorial strength in the service of a rigorous demonstration of the deplorable “absence of human solidarity” the filmmaker decried publicly, seamlessly and skillfully set up as an interlocking trap of wrongly attributed guilt–as the outstanding French critic Jacques Lourcelles has noted, guilt is De Sica’s dominant theme from I bambini ci guardano through Umberto D., and it’s worth adding that it keeps rearing its ugly head on a regular basis up to De Sica’s last films–consider e.g. his return to the war years in Il giardino dei Finzi-Contini (The Garden of the Finzi-Continis, 1970).

If I make Sciuscià sound perilously close to the artifice its creators decried with noble intentions–its overdetermination makes even the self-conscious coup de cinéma (the climactic projector breakdown in a suspense scene playing out during a screening for spellbound small prisoners) come off as a coup de théâtre–, I still can’t deny that Ladri di biciclette channels its dramatic energy into something different: its transfer-of-guilt-trip through the scarred souls and landscapes left in the wake of the war plays surprisingly close to a Hitchcock movie, with the plight of its everyman hero and his son on the trail of the stolen bike he needs for work transformed into a kind of moral thriller, in which the Hitchcockian role reversal with the thief is conveyed in a series of effectively staged suspense scenes (the bike search amidst crowds at the market demonstrates a successful integration of the neorealist impulse and genre elements, whereas the unpleasant confrontation in a church could be considered the counterpart to the finale of La porta del cielo in its carefully focused intensity). It’s hard not to think of a film Hitchcock made nearly a decade later, The Wrong Man (1956), based on a true story and directed as an Alfredian approximation of documentary realism, the pronounced soberness in style at loggerheads with its exalted religious fervor.

Did film history also enshrine the wrong man in “De Sica”? Approached in this context, it makes more sense to see his classics as ultimate triumph in popular filmmaking (even the seemingly unpopular dedramatization of Umberto D. is counterbalanced by a sense of constant movement), with the international success of Italian neorealism carrying his lasting emotional signature–although Sciuscià was initially considered a box-office disappointment at home, it rebounded elsewhere. It’s just that De Sica’s profile did not hold up to concurrent expectations of an artist with a capital A. Additionally, when a new generation of Art-Auteurs, from Fellini to Antonioni, became the rage, his immensely popular sex comedies with Sophia Loren and Marcello Mastroianni were considered populist sellout–De Sica never made amends that he did a lot of things because he always needed money (gambling, two families…), but that doesn’t mean he didn’t care: already in the Fascist years, a complex form of opportunism was always part of his stock-in-trade. A more productive pattern to view De Sica would be to align him with more comparable important figures that are still underacknowledged in today’s English-centric film culture: For one, there’s the influence of Mario Camerini, now probably most remembered for his Ulisse (Ulysses, 1954) starring Kirk Douglas, but a notable director already in the silent era. In the 1930’s, his petty-bourgeois-penthalogy of comedies with De Sica paved the actor’s rise to (romantic) stardom–and a piece of the road towards neorealism, starting with Gli uomini, che mascalzoni… (What Scoundrels Men Are!, 1932), filled with breathtaking glimpses of the era’s modern city life, Milanese-style and one of the great discoveries of the Film Museum’s current De Sica retro. Up towards I grandi magazzini (Department Store, 1939), Camerini and De Sica put their spin on the encroaching white telephone templates, always managing to smuggle some subversive notions–at the titular department store, consumer desires and crime are united.

But by the time De Sica arrived at his first solo directing effort, Maddalena… zero in condotta (Maddalena, Zero for Conduct, 1940), that subversion has little in common with Jean Vigo, instead presenting an elegantly executed reflection on the frustrating nothingness at the core of Il cinema dei telefoni bianchi as mandated by the regime: its escapist art deco designs to be built on wish-fulfillment, avoiding any overt mention of politics or social issues. Which brings us to one of Italy’s finest directors, Vittorio Cottafavi, closely associated with De Sica for a good chunk of the 1940’s. His outstanding debut I nostri sogni (Our Dreams, 1943) is an elaboration of the Camerini-De-Sica-concepts, with noticeable dark spots all over its white telephone veneer, attesting to Cottafavi’s touch, while the directorial involvement of his co-writer and star De Sica–playing an impostor, naturally–remains unclear; Cottafavi, in turn, shows up in La porta del cielo and together with star De Sica was the driving force behind another Zavattini-co-written and rather bizarre postwar film about guilt, Lo sconosciuto di San Marino (Unknown Men of San Marino, 1948), on which he is only credited as assistant director to Michal Waszynski.

Cottafavi would become part of the pantheon e.g. of the French Mac Mahonists, whose enthusiasm I find entirely justified. But even despite a resurgence in recent years, he unfortunately remains a cult figure at best, his automatic association with pepla as unhelpful as De Sica’s with neorealism. With Cottafavi’s second career on TV from the 1960’s onward–actually, the bigger part of his oeuvre–finally lifted from obscurity, maybe we could start backwards, and retrace it in tandem with De Sica, discovering parallel, yet entirely different developments, leading to a more sophisticated and nuanced understanding of (Italian) cinema. Also, I simply can’t wait to see Caccia alla volpe again–after all, these reflections have reminded me that De Sica milks its film-within-the-film subplot for all it’s worth with regards to auteurist pretensions in the shadow of neorealism. Far from the clear-cut idea of “De Sica”, his career has developed in mysterious and complex ways that haven’t been sufficiently acknowledged–and although he demonstrated in his eponymous movie that the very idea of a final judgment is always premature, beneath his always-upbeat popular image and his obsolete place in film history he clearly craved a deeper understanding of the times he lived in up to the very end. Accordingly, his legacy deserves a deeper look as well.

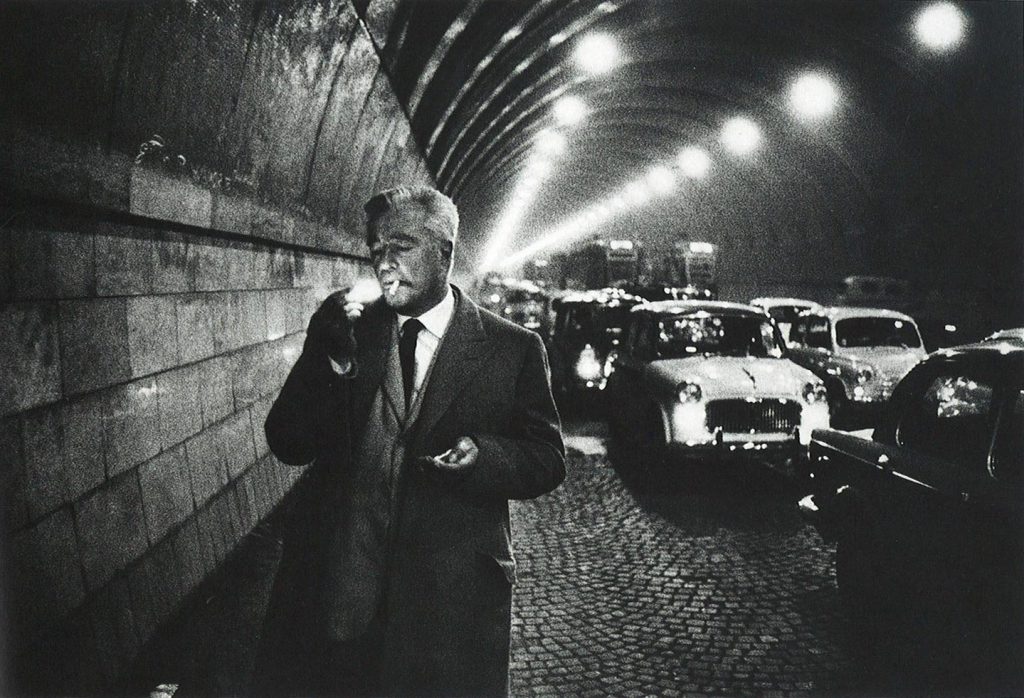

Photo: Federico Garolla