Christoph Huber

As our Godard retrospective opens, it’s time to consider the fact–Godard would surely agree–that everyone is (or should be) indebted to Raoul Walsh.

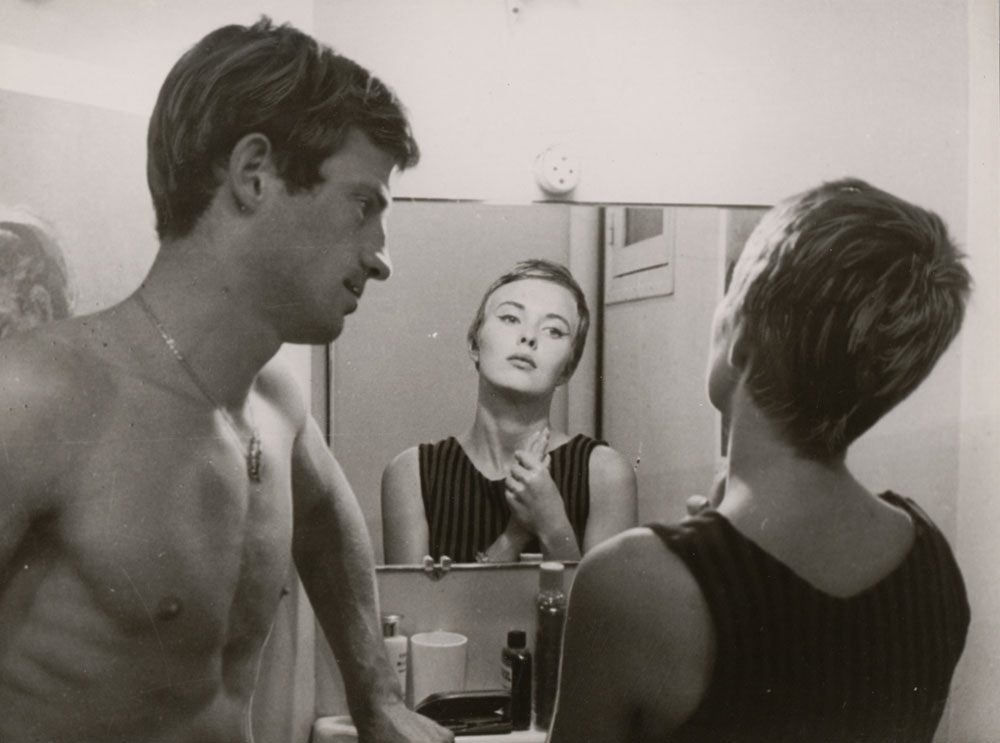

“Mister, what does it mean… when a man ‘crashes out’?”, the character played by Ida Lupino asks before the fade-out in Raoul Walsh’s High Sierra (1941)–its coarse echo in Jean Seberg’s “What’s that mean, ‘puke’?” one of the many film references Jean-Luc Godard crammed into his feature debut À bout de soufflé (Breathless, 1960), playing at the opening night of our Godard Retrospective Vol. I. Famously, Godard “invented” jump cuts with that film (which actually hail from the very beginnings of cinema–cf. the magic of Méliès), meaning he used them to such an extent they left an impact and became an accepted device.

Godard’s simple reasoning: “Since after thirty years [of living], people try to put everything into their first film. So they’re always very long. And I was no exception to the rule. I had made a film that lasted two and a quarter or two and a half hours; and it was impossible, the contract specified that the running time not exceed an hour and a half. And I remember very clearly… how I invented this famous way of cutting, that is now used in commercials: we took all the shots and systematically cut out whatever could be cut, while trying to maintain some rhythm.” (I quote from an article by Richard Raskin examining Five explanations for the jump cuts in Godard’s Breathless, well-worth reading if you’re interested, but for my purposes the fact suffices that Godard found a radical solution faced with the problem of an overlong film, violating a norm of classical movie editing.)

Less well known is an intriguing and not entirely dissimilar story I encountered in Growing Up in Hollywood, the first of the two highly amusing autobiographical books by Robert Parrish, focusing on his years as a child actor and editor–the equally recommended second book, Hollywood Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, picks up with his experiences as (still-undervalued) director. Along with the fancy tales of Raoul Walsh and the novelistic tome of Andre de Toth, Parrish’s more modest, but insightful books rank among the top autobiographies by filmmakers–I finally got around to reading them, when researching for our big John Ford retrospective last fall. Parrish served as an editor in Ford’s WWII Navy Field Photo Unit, cutting his teeth on The Battle of Midway (1942) and others. There are many priceless anecdotes about Ford in both Parrish books–the one about the Nuremberg assignment with the Russian Major turning out to be a Ford expert so good he repeats it in the second.

But I had never heard the story about Robert Rossen’s All the King’s Men (1949), a near-classic, which ended up winning three Academy Awards that year, including Best Picture, and netted nominations for Rossen (both as a director and as a writer) and Parrish (as co-editor with Al Clark). The way Parrish tells it, he was brought in to fix a shapeless mess that preview audiences hated, with studio boss Harry Cohn complaining: “My ass got tired about halfway through, and when my ass gets tired I know I got a flop”. For reasons elaborated on in an earlier Parrish chapter about Rossen’s previous success Body and Soul (1947), the director had shot enormous amounts of footage and couldn’t make up his mind about which parts to use, leaving Clark desperate. Parrish came in to reassemble the thing almost from scratch, but ended up as frustrated as Rossen after six months and seven more disastrous previews of what remained a two-and-a-half-hours behemoth.

At the last moment (or Parrish is just a good storyteller), Rossen has the idea to rerun a really good picture he’s written a decade ago–and is enthusiastic afterwards: “The reason that picture works is because it’s imperfect. It gallops along from scene to scene like one big ninety-minute montage. The audience never gets a chance to relax and think about the story holes. They’re into the next scene before they have time to think about the last one. I’ve got an idea for our picture.” Heading from the Italian restaurant near the studio to the editing table, Parrish applies Rossen’s advice to “what was still a slow two hours and ten minutes”.

Rossen’s radical solution: “I want you to go through the whole picture. Select what you consider to be the center of each scene, put the film in the sync machine and wind down a hundred feet before and a hundred feet after, and chop it off, regardless of what’s going on. Cut through dialogue, music, anything.” At 5 a.m., Parrish claims, “we had a ninety-minute picture. We ran it for Rossen and discovered that his brainstorm had worked. It all made sense in an exciting, slightly confusing, montagey sort of way.” (Parrish admits to adding bits to three scenes afterwards, but All The King’s Men is still 110 minutes long–well, nobody’s perfect.)

The old movie Rossen and Parrish rewatched? The Roaring Twenties (1939) by Raoul Walsh, obviously.

As a bonus, two loosely connected links:

David Bordwell on a radical King Hu Jump Cut

& Future Waves of Godard